ADVERTISEMENTS:

Motivations of the Individual in Society: Theories and Social Process!

While the behaviour of an individual explains the inner workings of his mind, there is some factor that shapes such internal workings; and this factor that determines the mental processes leading to the behaviour of an individual can be termed as his ‘motive’.

Psychoanalysts have forwarded several theories on the point and in fact, many have made distinct contributions in the field of the study of human motives. They speak of the conscious mind and its urges and also of the regions of the sub-conscious and its dictates.

Theories of Motives:

Sigmund Freud has probed the depths of the human mind and has discovered that certain unconscious forces in the human mind determine his motives. These forces have been termed by him as ‘instincts’, and human personality expresses the interaction of the instincts of Eros and Death, that is of sex and self-destruction.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The psychoanalytical view is that the interplay of these instincts creates in the individual certain ‘complexes’ or ‘fixations’ which remain active below the conscious level, finding occasional expression in ‘dreams’ or in erratic conscious behaviour. The psychoanalysts, therefore, look primarily for the ‘unconscious motives’ for which, of course, they take into account the conscious life history of the individual under study.

However, the Viennese physician has, in determine the theory of personality development, advanced a conception of the ‘self in certain divisions. In every individual, according to him, there is the ‘id’, the ego and the superego. The ‘id’ is the unconscious, primarily representing the primitive side in him in the form of his instinctive desires, including those of sex and death.

The ‘ego’ develops out of ‘id’ and represents such qualities of the mind that can control the ‘id” and help the individual in becoming conscious of his self. But no individual develops his ‘ego’ in a manner that is isolated from the influences of society. As the values and the norms of the society work upon the ego, the ‘superego’ develops unconsciously, and becomes what may be described as the conscience of the individual.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In understanding the psycho-analytical view of the workings of the human mind, we make an attempt at understanding human motives. McIver says ‘of all quests, none is more complex than the adequate understanding of motivation’. He is of the opinion that without any question Freud’s contribution to the understanding of motives is important; but motives of the self are only a part of the study of the sociologist.

An individual is only a part of the society and, therefore, man’s activities are necessarily related to an understanding of the society of which he is a part. Hence, other theories explaining human motives assume importance. McDougall forwards the theory that man is associated with certain ‘instincts’ that fundamentally shape his activities.

In his ‘Introduction to Social Psychology ‘, he expresses his belief’ that certain basic needs or drives mould the motive of the individual, and these needs or drives may be described as the constant conditions of the human nature. Even according to V. Pareto, there are certain ‘residues’ in human nature like those of combinations, group persistence, self-expression, sociability, individual integrity and sex.

These ingredients of human nature or ‘residues’, as he calls them, motivate human conduct, but occasionally certain ‘derivations’, which are none other than the human power of thinking and reasoning, can offset the direct influence of residues upon human behaviour.

Another view which seeks to explain motivation in human beings is that man is an economic being, as Adam Smith would have put it, and the motives that find expression in his behaviour are linked with his economic existence. Karl Marx is certainly a proponent of this kind of a theory explaining human conduct.

According to him, the class struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat effectively highlights the clash of economic interests between the two groups; and, in fact, all non-economic social factors like political, religious and the cultural ones are in the final analysis connected with underlying material interests. On a more moderate scale, C.A. Beard too emphasizes the importance of the economic motives in his Economic Basis of Polities’.

Whatever his motives be when an individual finds himself placed in the society and becomes a ‘social person’, he develops certain attitudes and interests vis-a-vis objects and personalities around him. Psychologists may be interested in making a difference between conscious attitudes and the unconscious ones and in having a similar difference for interests; but the sociologist will not particularly stress such points of difference.

He will be interested in the ways in which human beings regulate their relationships with each other. However, in every expression of human understanding through external behaviour, there is always an element of the ‘subjective’ and the ‘objective’. When a human being says that he is ‘afraid’, his fear’ is a subjective ‘attitude’ in the sense that it expresses the workings of his mind along a particular line.

But then a condition of being afraid cannot be created unless the mind has received a message from ‘objective’ or real surroundings that it must react in that way. When we say ‘objective’ or ‘real surroundings’, we do not necessarily mean natural objects only; such real surroundings may be represented by even a mere external phenomenon like excessive heat or cold or a clap of thunder.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The mind may, therefore, hold in fear such objects like a tiger, a dacoit, and thunderous conditions of nature or even a discussion of a delicate topic. Similarly, one may love a bird, a beautiful panoramic view of nature, or a delicate looking flower. If we understand this relativity between the subjective and the objective, we shall be able to grasp the relation between ‘interests’ and ‘attitudes’, human interests and attitudes in society and in the process of socialization of the self.

We have already considered in the previous chapter how the child become socialized, that is, how he learns to realize his ‘self in the context of the society in which he lives. In the same process, he learns to develop certain attitudes, beginning with the elemental stages of understanding in which he knows only the difference between objects that give him pleasure or pain.

As soon he becomes conscious of the fact that there are both objects and persons around him, he learns of social relationship, no matter how well or dimly he understands the significance of such relationship. ‘Attitudes’ develop in the process, always in connection with some ‘interest’ that the individual finds in society.

Such attitude may be directed towards, or against, a person, that is, there may be on his part an attitude of love for a person, or of hatred towards another. These personal attitudes develop a sense of adjustment between them in social life, whether it is the attitude of friendliness, enmity or tolerance.

Again, certain attitudes may be complementary in character, like the tender love of the parent for the child and the child’s devotion to the parent. We must also take into account the fact that while attitudes adjust relationship between individuals; correspondingly a set of attitudes arises in a group or a society in relation to another group or another society.

Whenever people share common social situations, they develop certain attitudes which are no longer mere personal feelings; they become group attitudes, as we have the attitude of the Hindu towards the sacred cow, or the Muslim attitudes towards the pig as an unholy animal.

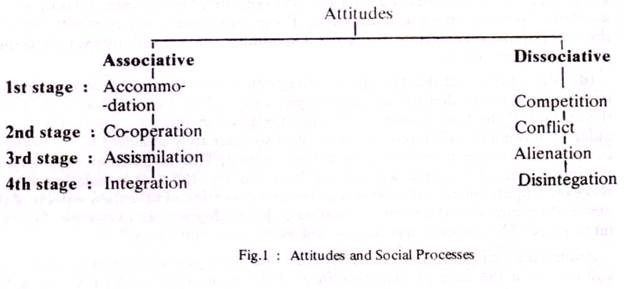

It would be wrong to apply any ‘static’ colour to attitudes, for human attitudes, for human attitudes are constantly changing and, in that sense, they are ‘dynamic’. However, instead of following the path shown to us by the complex formulations of theories of psychology, if we take the sociologist’s view that relationship between human beings are the decisive factor in determining attitudes, one may follow McIver and Page and classify attitudes as ‘associative’, ‘restrictive’ and ‘dissociative’ ones.

Associative attitudes tend to promote social relationship, restrictive attitudes limit such relationship, and dissociative attitudes prevent any relationship between man and man. For example, if a person or a group develops a sense of inferiority towards an object or another person or a group, the associative attitude would encourage in him or the group feelings of hero-worship, respect or gratitude; the restrictive attitude would be exemplified in feeling of awe, devotion or submissiveness; and the dissociative attitude would evoke in him feelings of fear, envy or bashfulness.

Similarly, when one feels indifferent to another, his associative attitudes are those of courtesy, sympathy and affection or kindness. The feelings of jealousy or rivalry would then explain his restrictive attitudes, while the dissociative ones would be found in senses of distrust, aversion, dislike or suspicion.

When one has a sense of superiority over another, he would pity the latter in his associative attitude, and disdain or abhor him, in expression of his dissociative attitudes. If he learns simply to tolerate the other, it would manifest his restrictive attitude in the circumstances.

Sociologists now attach considerable importance to studies of attitudes which seek to explain individual or group behaviour, whether it be a device to study the marketability of certain products or its is a gallup poll gauging interest in a-political party and its performances.

As the author writes these lines, the world comes to appreciate the accuracy of the opinion poll study made by British journalists in predicting the victory of Prime Minister Thatcher and her party in the elections. Yet one does not contend that all attitudes can be measured mathematically, although one sees round the world almost frantic effort at understanding ‘public opinion’ upon many different matters.

These matters range from the simple question whether or not an average housewife prefers one brand of detergent to another to questions of factors accounting for student or labour agitation, the problems of having large families in India and the efficacy of nature cure as advocated by Mr. Morarji Desai.

The success of these poll studies will depend on how impartially one can diversify his field of study, without restricting his attention upon or unduly emphasizing the importance, of, one section or the other of society. This condition of the study assumes extraordinary significance in a country like ours, when it covers thousands of miles of diversity.

Interests in a society determine the attitudes, and social experience then always becomes an adjustment of attitudes and corresponding interests. While our attitudes may vary on the personal level or at the group level, our interests too may be of a clear division.

McIver and page distinguish between what they describe as the ‘like” interest and the ‘common’ interest. The term ‘like’ is used for any capacity or habit that individuals have privately and individually, though there is a similarity in such habits or capacities. When a student develops the interest to study, he has a ‘like’ interest with that of the other student. Similarly, when a grocer seeks to earn profits by selling goods, he has a ‘like’ interest just as another grocer has.

Occasionally, we have certain interests that can be described as “common’ interests. No interest is common unless it is shared with another. Thus, when each student has the interest of doing well in an examination, each has a like interest since it is not being shared with that of the other. But when these students play a game with a team that is reckoned as an ‘outsider’, they have the common interest of defeating the outsiders. Similarly, when grocers or other men in business form an association, they exhibit their common interest not to be exploited at the hands of others.

When these common interests are applied to social life, we find that they manifest themselves in certain feelings like ‘group loyalties’. A person shares with another of his group the common interest of being attached to the group, be it a family, a city or a nation, for its benefit.

Attitudes may be developed from this sense of belonging to a group; on the one hand, there would be the associative attitude of affection, friendliness etc. for members of the group and, on the other, dissociative ones would express themselves in hostility towards anyone who does not belong to it. Prejudices and preferences are products of these processes.

Similarly, common interests may exist in a society in respect of certain aims in life, in certain pursuits of the intellectual and the cultural types. In the fields of science, religion or philosophy, members of a society may develop common interests in achieving common ends; and this process will ultimately show its centripetal and centrifugal tendencies.

Persons who are able to associate themselves to such ends will move closer to each other and develop a common bond between themselves and, at the same time, they will move away from those who cannot share these ends; and a clear cleavage between the two groups, say, between music lovers and those who find every musical effort a painful experience, will emerge.

However, the more we notice these trends, centripetal as well as centrifugal as has been described above, the more does the human society feel the urge for harmonizing the divergences between different sets of common interests, and a ‘like’ interest possessed by individuals to live peacefully is developing into a ‘common’ interest of sharing conditions of peace throughout the world, and we have already begun considering the possibilities of a world society living in peace.

Social Processes:

The ways in which human beings determine their relationship between each other in any society may be described as the social processes. According to certain sociologists, these processes may be either ‘conjunctive’ or ‘disjunctive’ in character. The conjunctive process tends to bring the different constituents of the society closer to each other, while the disjunctive one has the effect of keeping them apart.

According to Park and Burgess, social processes are capable of being any of the following:

(i) Conflict,

(ii) Competition,

(iii) Accommodation and

(iv) Assimilation.

McIver adds a fifth process to the ones mentioned, and calls it co-operation. Some writers mention ‘alienation’ as yet another process. In fact, human behaviour in relation to each other in society can express any of these six modes of moulding characteristics, and it is worthwhile having a look at each of these separately.

(i) Conflict:

Whether one believes in the evolutionary pattern of human society, or he looks around objectively to study how human beings bear themselves in relation to each other in society, the pattern of conflict as a social process becomes very clear. Wherever persons act with some degree of interest or the other, there must necessarily follow a conflict of interests unless they are such that their attainment does not call for a necessary disappointment for one when the other succeeds.

If we wish to have air and, perhaps, light, or if each person is interested in praying to God, no conflict will naturally arise; but if a particular interest cannot be attained by some unless others make a corresponding sacrifice, conflict becomes inevitable.

According to Kingsley Davis, a conflict must presuppose the adoption of an attitude by two persons or groups that if one of them has to attain economic or social success, the other must necessarily die, be otherwise discarded or eliminated. If this view of ‘conflict” is taken, the term can easily separate itself from the connotations of competition.

Kingsley Davis further maintains that conflict may be either ‘partial’ or ‘total’. A partial conflict can manifest itself in the very manner m which a particular objective is to be attained, though the constituents of such objective do not disagree upon the very objective itself.

Thus, economists may agree that inflation is an evil, but they may have differences over the modes of fighting it. If, however, any two groups cannot find any basis of agreement upon a matter of thought, their conflict is total.

The democrat’s views on the measures to be adopted for the improvement of the lot of the common man are not in any way similar to those of the anarchist or the dictator. Here, the two stand on entirely different footings.

McIver and Page classify conflict into ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ cases of conflicting behaviour. Conflict is direct when a person or a group of persons seeks to destroy or annihilate another in an effort to attain a goal, and direct conflict is exemplified in litigations, polemics, duels, street fights and, of course, in revolutions and battles. Conflict is indirect when each such person, in trying to attain his objective, hinders or obstructs the other person and tries to prevent the latter from attaining the goal.

Quite naturally, therefore, indirect conflict would have about itself the traits of civilized behaviour, and one finds such conflicts between two teams competing for a trophy, two persons fighting an election or vying with each other for winning an honour or a social title. While competition becomes an example of indirect conflict with McIver and Page. Kingsley Davis would not accept competition as a form of conflict. Davis further holds that society as a unified whole can be conceived of only when individuals learn to rise above their basic physical needs and regard a higher ideal as a necessity.

But there exists between man and man what may be described as personality differences corresponding to the difference between their respective cultures. The differences can be the very basis of conflict, for the conflicting interests or characteristics of the two will invariably create hostility or opposition of one to the other’s ideals.

If the nature of conflict is carefully studied, one finds that it has certain characteristics:

(i) The aim of conflict is to defeat or annihilate the opponent and, as such, it is a fleeting or a temporary sentiment;

(ii) Conflict is directly opposed to co-operation, for in a conflict one seeks to hinder and obstruct the other. It may not necessarily be violent in character; at times, it can be a well-disciplined activity like the movements of satyagraha or non-co-operation in our country;

(iii) Conflict is a personal quality, but it possesses a universal characteristic in the sense that all persons in all different societies experience this urge or sentiment, as it may be regarded.

In any society, one can find the quality of conflict assuming any of the following forms:

(a) ‘Personal conflicts’ arise from a clash of interests between two individuals, who seek to settle the issue in physical terms.

(b) ‘Class conflicts’ as may be witnessed in movement of a class against the other, are obviously connected with the motive of annihilating the other. Marx explains his class conflicts in terms of clashes that must determine who would gain material superiority.

(c) ‘Race or caste conflicts’ exist between groups belonging to different ethnic, religious even national differences. In our country, these differences have seen violent outbursts simply because one caste group has found another absolutely unsufferable.

(d) ‘Group conflicts’ exist between persons who subscribe to opposing economic, political even cultural interests. Usually, these groups engage in indirect conflicts, one against the other.

(e) There may also be cases of ‘international conflict’, as between two super powers over the question as to who would enjoy a larger sphere of influence.

It may be argued that conflict imposes a heavy cost upon society by being divisive in effect. It divides a group, community or a nation into two and can easily set brother against brother. How far-reaching the effects of conflict can be in this regard, we, in India, understand fully merely by referring to our history for the last fifty years.

Ireland, in this context, would not be another inappropriate example. Conflict is expensive; it is wasteful. War expenses can take a heavy toll of human comfort, and the after-effects of even a minor-scale war upon the Indian economy in the ‘sixties and the ‘seventies have been felt with anguish and alarm.

But conflict as a very natural mode of expression of human attitudes has an element of a silver lining too, which even its critics do not fail to notice. While any war is looked upon with suspicion and contempt by a humanitarian, no degree of wisdom can bear to ignore the feelings of loyalty that are evoked by it, in each warring group. No matter what element of dissent tears the society apart in peace times, as soon as there is external aggression all the factions close their ranks and work for the common cause of defending their country.

Besides this, conflict makes society conscious of its shortcomings and paves the way for social change. Now-a- days, it is common experience to find some national leader or the other denounce attacks upon, and prejudices against, Harijans and people belonging to Scheduled castes and Scheduled tribes.

This is indicative of an awakening of the conscience to the acuteness of the problem. Though there was a time when a show of contempt upon these people was regarded as a thing that was quite in order, the ferocity and the futility of the conflicts between caste Hindus and the ‘lower’ ones has moulded opinion in the direction of wiping out the social barriers between the two. In the United States, too, the race riots have carried with them consequences of similar significance.

(ii) Competition:

Competition is a variation of conflict and one may even venture to say that it is a later form of human behaviour developed with a consciousness that crude conflict can be wasteful and unmannerly at the same time. Every society whether simple or complex is based on the desire for orderliness in human affairs; and an understanding that the goal has to be attained with endeavour and not merely by brute show of strength is one of the achievements of civilization.

Competition can be defined as a type of opposition or contest between persons or groups of persons for obtaining a particular object or attaining a particular goal. According to Fairchild and Bogardus, if any object is scarce in supply, and persons or groups of persons desire to attain the object with an equal degree of eagerness, a conflict or rivalry between such persons or groups becomes inevitable; and competition becomes an orderly, civilized expression of the desire to fight or to battle for the object to be attained.

As we admit that competition is an ‘orderly conflict’, we necessarily take into account certain ‘rules of the game’ that regulate the modes of competition. Society lays down certain rules for a competition, and every competitor gives fight to the other according to those rules.

Thus, there are election laws which determine the limits to which candidates can go in trying to impress the candidature of each upon the electorate, and there are set rules according to which every cricket team will play the game in trying to secure a win for itself and ensure a defeat for the other.

As long as each contestant remembers the rules of the game, competition is based upon such rules and it assumes an impersonal character; but as soon as the rules are forgotten and the opponent becomes the target of attack, competition lapses into the level of a conflict, an ungarnished expression of the primitive desire to win by destroying the other.

Ogburn considers this type of conflict as ‘antagonistic to win by destroying the other. Ogburn considers this type of conflict as ‘antagonistic competition’. For example, if a seam bowler is not merely interested in securing competition degenerates into crude conflict. McIver, therefore, takes competition as a type of indirect conflict.

The following ‘characteristics’ of competition may be kept in mind in order to distinguish it from conflict:

(1) Competition is ‘impersonal’ in character since the aim of every contestant is to attain a particular goal. The identity of the rival contestant is not important in the game; every contestant is concerned about the success (or the failure) that will crown (or ruin) his efforts.

(2) The element of impersonality about it brings in another factor that shapes competition, and that is its “universality”. In every sphere of social activity one “notices competition, whether it be among students or sportsmen vying for a cherished trophy, between artists or professionals, or between manufacturers, labourers and other agents in economic activity.

In fact, if organization grows up in respect of any human activity, competition between organizations becomes inevitable. Producers’ associations, labour unions, political parties and even independent nations compete with each other in this sense of the term.

(3) Competition is an ‘endless process”, not terminating in the outcome of one fist- fight or one bout in the match. Matches may be played in a competitive spirit, no doubt, but no match decides the outcome of a competition in the sense a duel or a bare, primitive fight between two individuals determines.

Even after the match or a series of matches is concluded, there will yet be other encounters, and the end of competition is not visualized in human society that is both aspiring and dynamic.

(4) Competition has its ‘psychological advantages’ too in so far as a spirit of competition must necessarily rule out an attitude of defeatism. Battles, contests and sports encounters are not always won or lost with mere physical attributes or the inadequacy of them; the spirit that knows how to challenge, and how to spurn retreat, progresses with indomitable courage towards the goal. Competition alone can foster this spirit, for it carries with itself the promise of success and inspires even the weak to positive action.

(5) It follows, therefore, that without competition, society would have remained static, and this very competitive spirit brings ‘movement’ into the social processes. Today, when science and technology rule not only our heads but our hearts too, the competitive spirit has fostered operational efficiency on both personal and national levels and has made room for successive innovations.

On the personal level, particularly, the satisfaction that successful competition brings along can inflate the ‘ego’ and further induce the individual to unlimited advances in his achievements.

(6) Since competition aims at the attainment of certain objectives in an orderly manner, it will ultimately tend to ‘equitably distribute the social resources’ among as many constituents of the society as is practicable. Since the means of obtaining the resources are open to all, no undue concentration of social wealth and resources would be facilitated by competition.

But as Kingsley Davis points out, an unrestricted competition in which the contestant unfeelingly clings to the means of attaining his goal, without any regard for any other factor, can bring about a condition in which the strong will tyrannize over the weak, and the influence of the former over the latter will destabilize the social balances.

Competition whether personal or of different groups, can arise in different spheres of human activity. On the impersonal level, the most prominent forms of competition are those related to economic or political activities. National and international politics are not totally delinked from each other, arid the formation of three distinct ‘Worlds’ now-a-days is indicative of a fierce competitive spirit that exists in different nations along political lines.

Modern politics being based on economic principles and considerations, political competition necessarily goes hand in hand with economic competition. Racial competition, or competition between different races for supremacy, was a prominent feature in the history of mankind in the past times, with at least one national leader of the twentieth century trying to revive the concept, causing much agony to the human race; but now-a-days the limits of competition have transcended mere race lines and other more secular considerations have assumed importance.

Social or cultural competition is the most refined of all the different competitive pursuits though, at times, reactions to this type of competition can assume savage proportions. In general, there is no violent reaction to an individual’s attempts at joining social prestige, since his merits will to a vast extent determine the outcome of his attempts; but if such attempts are made by a person of ‘lowly’ status in a society that is crudely conscious of status distinctions, reactions from the privileged and the established may become violent and ruthless and may totally vanquish such person’s high ambitions. As a result, social competition may produce conditions that will become highly explosive and consequent social disruption is not fully unimaginable.

(iii) Accommodation:

We have already seen that attitude may be associative or dissociative in nature. While dissociative attitudes reflect themselves in conflict and competition, accommodation is the first step towards association in society. Accommodation begins where conflict ends, and the desire to adjust on self to surroundings or conditions that are not entirely congenial finds expression in behaviour. Man finds it advantageous to terminate conflict or hostilities for the time being or for an indefinite period in favour of a condition that would facilitate peaceful co-existence.

Accommodation does not usually solve the problems that arise from the differences that cause the conflict, but it admits of an understanding of something that seems to be common in palpably different conditions. One may, therefore, define accommodation as an agreement between conflicting persons or groups for a minimum degree of co-operation between them, without necessarily deciding upon the differences that have made them hostile to each other.

McIver and Page give even a wider scope to the term when they maintain that man accommodates not only with other human beings but with external surroundings also. W. G. Sumner reminds us of the fact that accommodation as a social process does not settle differences; it merely helps people to live in differences. Hence, he feels that there is an element of ‘hostile co-operation’ in accommodation.

Human beings co-operate when they agree to work together for the attainment of a common goal; and they accommodate when they realize that their negative efforts at warring with each other are being unproductive.

Accommodation, therefore, is the first step in association of men, followed by co-operation. It helps to obliterate the differences, and reduce the distance, between groups or races or nations with different ideals and paves the way for a greater understanding that will in due course introduce the co-operative spirit in their behaviour.

The accommodative behaviour of the individual in society may manifest .itself in different ways. Unless differences in thoughts and ideas find some sort of adjustment, social living becomes impossible. Parents and children adjust with each other as soon as they realize that opposition by one to the other’s ideas will not pay in the long run.

The fact that legislators have a ‘speaker’ between them, or players have a referee to decide upon their differences, indicates that all these persons are eager to bring some harmony into their respective differential attitudes. Hence, accommodation may take different shapes and forms under different circumstances. When individuals tell each other “let us agree to differ”, they are agreeing to accommodate with an understanding that, if they cannot resolve their differences, they may at least ‘bury the hatchet’.

This agreement may endure for a length of time or it may be short lived; and, in determining the character of which, the national traits of the parties to the understanding may be taken into account. If the individuals have an ingrained passivity in their character, this type of agreement may last long; but if the parties are quarrelsome and aggressive in nature, they will soon remember their differences and act upon them.

In India, the passive character of our people helps them to live in peaceful co-existence with ideas and ways of life that are totally foreign to them and, therefore, unwelcome. Nations that go to war over different issues may embrace a period of truce for a while, but they are by no means unwilling to return to a state of hostilities, each to vindicate his own position.

The other word for peaceful co-existence would be toleration. Toleration is an attitude of accepting a condition as different but also inevitable, and this attitude also seeks to bring to an end the desire to go into a conflict over such differences. For example, as Swami Vivekananda said, once it is accepted that the purpose of religion is to formulate the relation between man and his Creator, it will necessarily follow that every religion has a common purpose.

If this understanding is achieved, persons subscribing to a particular faith will not find it difficult at least dispassionately to respect other faiths, without necessarily subscribing to them. Toleration, however, does not help to remove differences; it teaches that differences arise in the natural order, and the socialized individual must accept them as a part of life itself.

Other forms of accommodation manifest themselves in settlements and compromises, in mediation and in arrangements of super-ordination. Compromises express the exact measure of ‘give-and-take’ in accommodation, for each party remains willing to sacrifice something in order to buy peace.

In this sense, compromises may be made at home, in offices and large organizations, and in all spheres of indirect conflicts. Mediation is a process that invites outside assistance in making settlements and, in this case, the parties do not themselves find any way of shelving their differences till a third party helps them to an understanding.

For example, when the management and the labour in an organization have a dispute, now-a-days it is customary for the Government to mediate in it and help the parties in arriving at a settlement. The referee of a match may play the same role of a peace-maker between hostile players of different teams, and so may the college principal appear in disputes in educational institutions that are not very infrequent these days.

Super-ordination is a condition in which one of the parties has of necessity to admit that he is in an inferior or a subordinate position and, as such, in order to avoid greater distress, he must agree to the terms of the superior. Such conditions may arise after a positive result has been obtained in a conflict, as when the victor in a battle imposes terms upon the vanquished.

Similarly, if the labour union finds the management rather strong in its position, the union will accept terms laid down by the management without aggravating the consequences of a conflict and leading them to a crisis. If two warring factions, however, are of equal strength, a kind of accommodation will be evolved; but it will better be known as a compromise. Super- ordination as an arrangement is rightly understood as an unequal compromise in which one of the parties gains a clear advantage.

(iv) Assimilation:

We have seen that when an individual finds different cultures at play before him, he faces a culture-conflict. If he is unable to adjust or adapt himself to a culture that his not his own, and with what he is confronted, he becomes a ‘misfit’ and psychological complexities may arise in his personality.

Our associative attitudes may help us to see eye to eye with things that are new, and we may understand that for a good social living we need not only an accommodation with new conditions, but something more positive. If each person were to maintain the standards and the demands of his own culture only, social equilibrium would be threatened and society would be destabilized. What society needs for its better functioning, particularly now-a-days when any one society becomes a conglomeration of heterogeneous elements, is assimilation of ideas and cultures.

Assimilation can be described as a process of adjustment between two different groups in which the ‘differences between them ultimately disappear’. American sociologists consider assimilation as an important process in the development of their society, when they bear in mind the fact that streams of immigrants have arrived at different times in the mainland of America and they have had to “integrate” themselves to the American way of life.

In India, too we have had waves of invasions and conquests and, until the British came, the process of assimilation was almost unique for every invader thought of settling in the country and becoming an Indian. After initial difficulties, all the different ethnic or religious groups adopted this process and with the passage of time a sort of integration took place. The British, however, came as the ruler and preferred to be known as such and, therefore, the Indian has never been able in the true sense of the word to assimilate himself with the British Culture.

It remained ‘foreign’ to him always and he always suffered from a distrust of his ruler’s intentions and feared a cultural conquest besides the political one. Moreover, the British never remained in India as an Indian and, as such, the question of assimilating one’s way of life to that of the Britisher never really arose.

The question of assimilation arises when one has to live under conditions in which he cannot avoid the impact of a ‘foreign” culture and that generally happens with immigrants in a country. The newcomer finds everything strange but overwhelmingly true and positive, so much so that he cannot obviate its courses. It is true that Poles, Greeks, Puerto Ricans and others in the United States at first sought to maintain a type of a separate identity, but finally this dissociative attitude was not found to be useful.

Assimilation as a process is as educative in nature as socialization itself is. The difference between the two, however, is that while socialization as a process conditions a child to the demands and the tradition of his own society, assimilation comes as an advanced education for an individual who is already acquainted with certain distinct ways of living; it is, as Park and Burgess maintain, ‘the ability to share the attitudes and experiences that are common to the other group’. However, assimilation as a process is not purely an individual endeavour; several factors external to an individual help or hinder the process.

Factors that hinder or obstruct the process of assimilation are the following:

(1) Basic cultural differences may be so wide that no degree of integration is possible. The oriental and the occidental ways of life are different in a number of respects and the cynical attitude of Rudyard Kipling is not the only appreciation of the fact; the conflict between the two cultures has had telling effects upon the Indian society, and there are not many countries in Asia and Africa that have been able to adapt themselves to undiluted Western standards.

(2) Ethnic differences and differences of complexion and other physiological characteristics can be a major hindrance to the process of assimilation. The element of intolerance in the White man’s character as regards the Negro, the Black, the Nigger or the Coloured man is so conscious and active the even after centuries of efforts at living together, a true assimilation has not taken place; and the utmost that can be achieved in this line in some kind of an accommodation, of toleration and nothing more.

(3) The immigrant himself may suffer from an ‘isolationist’ temperament. Jawaharlal Nehru once said that Indians are rather insular in habit, and we do not wish to open ourselves out and mix with others. This trait of character is noticeable among peoples of different nations, not always without its beneficial effects. The Jews as a nation have always maintained their identity over several centuries and it has at last paid them dividends; but this isolationist attribute can never help in assimilating one’s own ways .with those of others.

According to McIver and Page, there are certain aids to assimilation; in other words, there are a few factors that help the process and these can be stated as follows:

(a) The stage of the development of the host society will be an important factor in conditioning the immigrant into it. If the level of development of the former is high or highly technicalized, and the immigrant has not had the advantage of a developed culture, the process of assimilation will be hindered. Thus, a West European will find the surroundings in the United States much easier that an Easterner.

(b) If the immigrant is skilled in his occupation, he would be more welcome to the population of the host country than the person whose level of attainment is low. When rural people enter urban settings, they find it difficult to adjust themselves to the adopted surroundings, in which their pressure is not considered to be a blessing.

When earlier in the century Italians, Greeks and Poles migrated in large numbers to the United States, they found it difficult with their agricultural occupational skills to suit themselves to the demands of a highly industrialized society.

(c) The number of immigrants and the role that they play in their host country will be another factor of which we shall take serious note. The United States encouraged immigration in the 1870’s and 1880’s in order to meet the demands of its industrial activity.

Great Britain too accommodated immigrants as long, as it could offer to them jobs to which the local population did not aspire or for which they considered themselves to the unsuited. But now, when the supply of immigrants has far exceeded the demand for them, anti-immigration sentiments are becoming very pronounced in a number of these countries.

At the same time, we must note that in any country these sentiments do not find any considerable expression if only a small number of persons arrive as immigrants. These ‘newcomers” are even welcomed by the host population and they, being small in number, show a willingness to become a part of the host culture.

(d) McIver observes that though the immigrant in the first or the second generation tries to maintain its identity, succeeding generations find it easier to assimilate with the culture of the host country. It has been noticed in several cases that while the older man remains indifferent or, at most, dispassionately attached to the adopted culture, the younger man feels quite at home with it.

This happens not only because the immigrant takes to the ways of the host country; the host population also, in however imperceptible measure it may be, gets conditioned to certain aspects of the new culture introduced into its soil and, in different degrees, an exchange of culture takes place. This process may also be described as ‘acculturation’.

Assimilation can take place even between small groups within the range of a single culture, as in the case of disappearance of differences between rural and urban populations of a particular country. As the rural population gets more and more urbanized in its ways, a type of assimilation takes place which has also been described by sociologists as ‘acculturation to urbanism’.

It is necessary in making a study of assimilation to refer to at least two factors that may be regarded as its characteristics. Assimilation is a matter of degrees and, whether one considers it on the personal level or at group levels, one finds that different individuals and different groups react in different measure to the process of adjustment. Not only that different generation possesses different degrees of ability to adjust, but among persons having a common background we can notice different degrees of assimilation.

A generalized but unconfirmed view in this respect is that women can adjust more than men do, but we have no scientific basis for making such a statement. Again, assimilation is never a complete process; it is a process that is always continuing and a complete achievement along its lines is more an idealistic concept than a reality. Just as adjustment between man and wife is never complete, groups, races and nations follow certain principles of compromise without being able to lose the identity of one in the other.

(v) Co-Operation:

Co-operation is a conjunctive social process that rests upon the desire of certain persons to work together, in order to attain any individual or a collective ‘goal’. The desire to co-operate may arise, therefore, out of like or common interests. When the interest is that of furthering the interests of the family, of a community or of the nation itself, a common interest comes into play and men can co-operate to protect and advance such interests.

The urge for co-operation may arise spontaneously from one’s emotional consciousness that he belongs to a particular group, or it can be fostered by the head of the family or by a leader of the community or the nation by inspiring individuals to certain standards and forms of behaviour.

Man realizes then that it is better to co-operate with each other for the attainment of their goals than to strive individually or separately. Even ‘like’ interest may bring men together in a mood of co-operation. The interest that every employee has in maintaining the security of his job will bring him closer in co-operation with the other employees, and they will behave in harmony in protecting the like interests of each.

Similarly, even though every producer of goods is, in some sense or the other, a competitor with the other, producers and manufacturers may co-operate for obtaining advantages from the Government and maintaining the cost levels of materials and labour.

There is, however, an important point of distinction between cooperation that is rooted in common interest and that which is caused by a like interest. Like interests cannot create intense feelings and passions about co-operation. The desire to serve an establishment or to earn profits from sale is basically a self-limited desire, and the concern for the other man in the field is limited by considerations that attach primary importance to the benefit of the self.

Common interests are, on the other hand, shared throughout, and families, communities and nations can passionately and fanatically learn to follow certain goals in utmost co-operation, the ‘self ‘remaining totally subservient to the interests that are shared. Hysterical declamations made by national heroes against the common enemy and dogged tight-lipped endurance on the face of severe persecution, as of religious groups, characterize the expression of co-operation that is based on common interests.

Taking several examples of co-operation into consideration, one finds that cooperation may be of two types: ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’. Direct co-operation means that persons come together to execute some type of work, that is, they do like things together. For example, when people play together or do a particular work together, it may not necessarily mean that the work cannot be done individually or that each of them cannot play individually.

One may play in the garden all alone, or he may dig the field for cultivation purposes; but if the work is done together with other persons, the condition of social contact gives them satisfaction. Besides that, the element of co-operation in our behaviour becomes prominent when we face difficulties in our task; if one man alone cannot put up a tent, he would quite naturally seek the help of other men.

Indirect co-operation in society stands for all such activities which men perform to a common end and with a common purpose. These activities do not have their individual or isolated relevance; they must be of collective importance. The running of the administration in a company or working on scientific research will be examples of indirect co-operation.

In these cases, co-operation is indirect in the sense that though each of the persons co-operating in the act has his own role to play, each such role is important in the context of the relation that it bears to the other roles in the functional complex. Every scientist works in his own project, but their works are taken together to ascertain the degree of scientific development achieved by the society. A minister as well as the secretary to a governmental organization in this way engages in indirect co-operation with each other.

Co-operation may also be described as ‘overt’ or ‘covert’, according to the circumstances in which it becomes necessary. When people write with the common purpose of eradicating the evils of the caste system, or when they group together to fight an epidemic, they overtly or expressly co-operate with each other.

If, however, two apparently conflicting or antagonistic groups subscribe to common ideals and norms which both hold as sacred and strive to preserve, there is covert or implied cooperation between them. For example, legislators belonging to the Government apparently are in conflict with the members of the opposition, but the two groups together co-operate in upholding all the principles and conventions relating to parliamentary democracy.

(vi) Alienation:

One of the dissociative processes in society is alienation, that is, the final parting of ways between two distinct ways of behaviour or two cultural set-ups. It stands for the rejection by a person belonging to a culture or way of life of another culture or a different way of life. In alienation, not only that a person insulates himself with the standards of his own culture, but psychologically, he establishes a sense of superiority about his own way of life and tries to maintain it as distinct from the foreign culture.

Even in occupational spheres, one notices alienation as a psychological complex in the worker, who begins to resist his work after much repetition of it as something which is hostile and inimical to his well being. Alienation is a dissociative attitude and an extreme one for that matter. Just an assimilation is the utmost that can be achieved in the associative spirit, alienation is the last stage in dissociative efforts.

The age-old policy of non-co-operation among Indians is indicative of this spirit.

Figure No. 1 may help to understand the different stages of social processes according to either the associative or the dissociative altitude: