ADVERTISEMENTS:

Principles of Heredity and Environment:

The principle of heredity asserts the fact that the blood of the parent flows in the child and as such conditions the individual characteristics of the latter. The principle of environment as a determinant of individual character traits holds, on the other hand, that man’s physical as well as social surroundings shape him more than any other factor does.

Instead of ascribing importance to-each of these factors, a number of writers have sought to establish the supremacy of each over the other, some saying that heredity determines the individual and others maintaining that environment can negative the qualities of heredity. There must be a suspicion in the minds of even the most open-minded that hereditary traits are distinctly found in the offspring, but opinion is not one on the exact extent of influence that heredity would have on a man.

Francis Galton wrote in 1869 that children can be expected to be of distinct merit when the parents are endowed with intelligence and noticeable skill. Karl Pearson in his Nature and Nature, held that heredity as an influencing factor upon man is seven times stronger than environment. The issue of heredity, in fact, cannot be isolated from the study of genetics, or the influence of peculiar characteristics in individuals known as ‘genes’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Gregor Johann Mendel, an Austrian monk (1822-1884), first spoke of the genes and the importance of genetics in the study of hereditary traits in man. The study of genetics has undergone much development since Mendel told the world about it in the nineteenth century, and in 1968 Dr. Hargovind Khorana obtained the Nobel Prize by enunciating his DNA theory relating to genetics, and we may assert that the influence of ‘genes’ of the parents conditions the physical structure as well as the physical growth of the child.

Mendel asserted that any one pair of characters may be inherited by the child, even though other trains of the parent may have been simultaneously transmitted to the child. According to Dr. Khorana, the acid in the human being abbreviated as the DNA is contained in certain-basic materials in the chromosomes of the nucleus of the cell; it contains the genetic code and is capable of transmitting the hereditary pattern.

In the United States, followers of the principle of heredity have even applied psychological tests on persons in order to find out whether or not differences in the levels of intelligence follow any definite pattern in the lines of race, nationality or even the family background.

The Soviet agronomist, T.D. Lysenko, and his follower, Michurin have emphasized the importance of environment over heredity; and this approach to the study of the individual can be regarded as faulty in the same measure in which other writers clearly seek to establish the supremacy of heredity If we follow Mendel and other subsequent scientists who have developed the principles of genetics, we would find that heredity in its purest and completes form can not affect the individual, since in each generation one-half of the genetic qualities of each parent is rejected and no family can be said to be continuing its undiluted characteristics over the generations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But that is not to say that heredity is fully conditioned by environment. Birth is an important factor, even as the law considers it; but birth alone has not been a strong determinant of the individual’s qualities. Scientists in the United States who have studied and applied the principles of ‘Eugenics’, particularly in relation to the White and the Black, have observed that the whites possess germ-plasma excellence of certain qualities which the Blacks do not.

Similarly, the intelligence quotient in the White has been claimed to be higher than that found in the Negro. Physical traits like height structure have also been measured and several writers have sought to point out racial differences in the matter. The physical traits are perhaps more concrete and may, therefore, be measured in practical terms; mental traits are measured by applying tests that are known as ‘intelligence tests’ and ‘scholastic aptitude tests’.

These tests take children of the same age-group and truly examine their knowledge. Neither can these tests be regarded as generally representative of the different races or nationalities, nor can it be said that they are impartial in the sense that they examine knowledge or intelligence in equal measure, bearing in mind the fact that the candidates may come from different backgrounds, while the questioner has his own shape of mentality in framing his questions.

The United States being a country where social mobility is a definite factor in its social structure, the principle of heredity easily takes upon itself certain limitations as to its application. Surveys made in that country upon occupations and relative intelligence positions have shown that persons in higher groups of occupations score higher in intelligence tests, and that the better educated and the well-placed in society, occupation wise, are more intelligent.

Studies made on distinguished families and the notorious ones may apparently indicate certain definite lines of family behaviour, but these studies must be taken with utmost caution before any pronouncement is made in favour of the principle of heredity, for neither do we have analysis studies of a large number of families nor can we divorce each such family studied from the environment in which it is nurtured. A family that finds all the advantages of being well-placed in society no doubt will produce .some distinguished

persons, and the son of a criminal who does not get any opportunity in society may tend to be another criminally minded individual, but this in no way will establish an agreement in favour of the principle of heredity. According to McIver, the entire matter is too controversial to justify any definite conclusion as to the relative importance of the two principles.

McIver gives us certain examples to show that whatever the strength of argument of one of the principles be, the other cannot be negative in importance or rendered insignificant. Twins that are born of the single ovum are termed as monozygotic’ or identical twins; those that are born of different ova are known as ‘dizygotic’ or fraternal twins. Among these, the ‘identical twins’ may have almost exact resemblances not only in physical appearance but in mental traits also.

Yet in no way can it be said that identical twins will possess common traits of individuality, even though they have been reared up in different backgrounds. Studies have shown that even though common heredity be established, there may be differences in the mental process and temperament, and the cases listed by H.D. Carter in his Intelligence: Its Nature and Nature show that if identical twins are reared apart, they show significant points of difference in their mental attitudes or intelligence levels.

Some researchers on the point have even noticed that physical traits may be affected by a ‘change of the environment’. Yet none of these studies has established that a change of environment changes the child completely so as to distinguish him as a person totally different from his twin brother. Some similarities remain even though the environment is made to be different.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The cases studied earlier of Kaspar Hauser and of Kamala, the wolf-girl, would help to emphasize the role of environment in life. Other studies have aimed at assessing the importance of environment by observing the effects of common nurture upon children coming from different families.

These studies have shown that children who have had the fortune of entering families and homes of a higher standing than the ones in which they were born have, in fact, shown marked intellectual development in contrast with those who have not had such opportunities. Researchers on the point, therefore, are inclined to say that intelligence responds much more to environment than to the mere factor of derivative power at birth.

The truth of the matter is that individuality is conditioned by both heredity and environment, and to accept one in rejection of the other would be faulty and unscientific. One must remember that the qualities that are being termed as heredity are not a growth that had nothing to do with environment.

The sociologist is not interested in the biologist’s inclinations for associating certain attributes like dark hair and brown skin with certain races only; his interest lies in matters that condition the social behaviour of the individual. The sociologist wants to find out how a person, or a group of persons, after being brought up in certain surroundings reacts, or react, to a change in such surroundings, either if conditions in his own society change or he himself enters a different society.

There is a general admission that changes that are introduced later in life do not much change the individual qualitatively, and an early change can have overwhelming effects. Yet the effects of industrialization have shown anywhere in the world a general acceptance of practical standards and a consequent matter-of-fact conditioning of life even among agriculturists.

All the qualities of life at its inception may be found in heredity, but environment introduces complexities in life at different stages and the plasticity of life takes it through different phases of development under the direct influence of environmental conditions.

The Physical Environment:

The physical environment of man may be taken to include all such geographical conditions as man himself is basically unable to alter. Leaving aside the cosmic forces including the laws of gravitation and such other principles which are associated with our planet in general, one may look at the earth’s surface and the soil which have, since times that are not exactly known to us, helped man in concentrating his habitation.

There is a general understanding that man has always sought the presence of water in any locality in which he wished to settle, whether the terrain was mountainous and rugged or flat. The climatic conditions have also been an important factor to give consideration to, and some of these factors have not been subject to any change made possible by technology.

According to McIver, certain natural factors are uncontrollable by man, and these include the relation between the sun and the earth, the land mass itself, the rivers, the seasons and the geological qualities of the earth in various places.

But there are controlable factors, too, in the sense the man been able to control and alter some of the conditions of his physical environment. Besides controlling the natural qualities of productivity of land, in the efforts of which he has even able to change deserts into verdurous regions, he has selected for himself such natural produce only as will help his social and economic institutions.

All that he needs for sustenance in life is produced on a large scale by him and at the same time, he holds equally important the cultivation of such materials as he needs commercially and economically, such, as, jute, rubber, lac etc. The fantastic rate of agricultural growth in the United States in the last couple of centuries has opened his eyes to the possibility of drawing out of earth much more than would have at one stage been imagined.

The geographical school of sociology, led by writers like Friederic Le Play and F. Ratzel, seeks to establish a very close relation between human society and geography. These writers and others following them believe that not only human settlement, but his economic, cultural and scientific considerations are all based on the geographical conditions that he finds around him.

Their emphasis is upon favourable conditions that help human habitation; and the influence of such conditions, according to them, upon the structure and growth of social organizations and institutions are great. Ratzel’s writings went even to the extent of developing ‘geo-politics’ as a principle of politics related to geography according to which political expansion would be based on the sheer need for physical space.

Geo-polotics also emphasizes the need for the study of the geographical conditions of other countries for political advantage, and it is argued that no country can even think of successfully waging a war against the other without having any idea of the geographical conditions obtainable in the latter; and the protagonists of this school of thinking would readily refer to Napoleon’s plight Russia before his fall.

McIver takes the reader through the rise of several civilizations of the world to show that geography alone never determined their growth. The geographical conditions under which the Mohanjodaro civilization or the Egyptian or Summerian civilization grew are not the same as those that attended to the growth of the Mayan civilization.

The author admits that in olden times people had to depend upon local conditions, food products and whatever was available from the immediate neighbourhood, but his faith in projects like the Tennessee Valley Administration is so great that he maintains that as civilization grows, the direct influence of geography on man’s life is minimized. Man-made factors have now assumed much importance in human life. On the one hand, technology and the diffusion of technological knowledge minimize the geographical importance of physical conditions, and, on the other, political barriers between countries rear up within each political state a civilization that cannot be said to depend on different physical conditions.

Again, McIver observes that man has gained immense mobility these days and he can easily move from one condition of geographical influence to another to suit his particular needs, and no longer can it be said that he is limited by geographical factors.

But we shall not negative the importance of geography in human affairs. Physical conditions such as geographical factors may be regarded as one of the determinants of the shape of human society, though not the only one. By and large sociologists agree that geography has its own influence in at least certain spheres of life.

It may be stated that there is a very direct influence of geography upon:

(i) The physical conditions under which man chooses to live;

(ii) Physique and the mentality of human beings, including their intelligence, and

(iii) Certain special qualities that may easily distinguish one society from another, including distinct food habits, preferences in attire etc.

A study of world population and its distribution will show that such places are densely populated which provide the means of sustenance to the utmost with minimum possible efforts. No sociologist can deny the fact that human beings concentrate more on flat lands and near rivers than on rough mountainous terrain.

Man, therefore, in choosing his habitat will have to condition factors affecting his housing, the cultivation of crops, the availability and the possibility of exploitation of animals and the proximity to, or distance from, the animal world. Technology changes these conditions to a great extent, but cannot totally negative the basic factors that create these conditions.

Therefore, taking population concentration as an indicator, we find that the agricultural zones of the East are the most densely populated, and next come the industrialized areas of Europe. While the United States maintains a more or less favourable balance between population and habitable land-area, there are some countries like Australia which are very thinly populated.

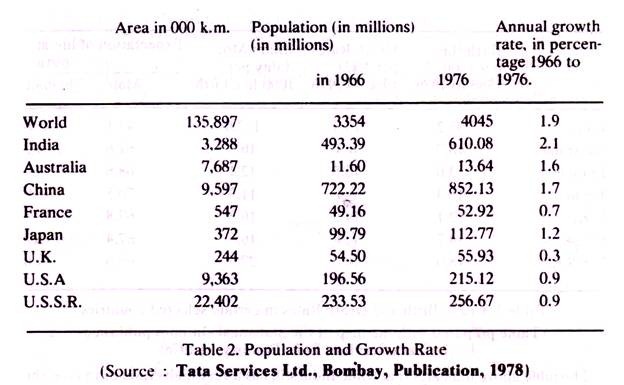

The tables given below will be indicative of the size and distribution of population in some of the countries of the world:

From the above table it becomes clear that certain countries are very densely populated as in the cases of India and China, whereas Australia’s physical size is more than double that of India and its population is only 2% to 3% of the Indian population. In India, the average density of population is 177 per sq mm (in 1971) and this figure also varies as we travel from one part of the country to another. West Bengal having a much higher density and Rajasthan a lower one.

China and the United States have almost similar land areas for each, but the population in the former is about four times that of the latter. Japan is an eastern country which has the benefits of a superior type of industrialization, but its population is much higher than that of the United Kingdom, the geographical conditions of which are said to be fairly similar to those of the former.

According to the Census of India, the Sex Ratio in India in 1971 was 930 females to every 10(X) males. The state of Kerala has the highest number of females according to the ratio, 1016 females to every 1000 males. Among the Indian states, Sikkim has the lowest number of females, it has for every KXX) males only 863 females. However, the number of females in Andaman and Nicobar Islands is distressingly low; for every 1000 males, these territories have only 644 females.

Dependence upon agriculture is almost associated with larger populations, though history affords us instances which would not permit the making of such simple statements. West European nations and the United States have witnessed population growth caused by improved technology in agriculture and gains of new commercial and transportation conditioning.

Other factors, that have helped population growth in countries other than the agricultural East, are improved sanitary conditions and medicine and the democratization of the political institutions.

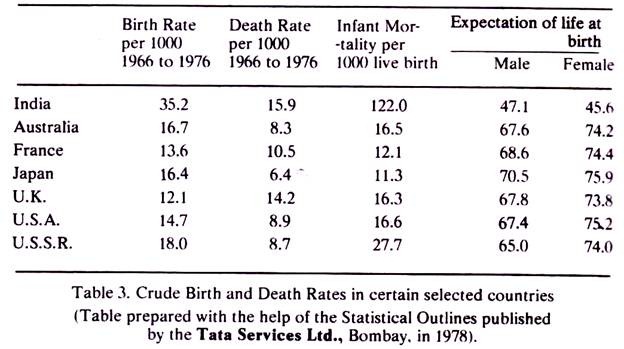

The average crude birth-and death-rates in certain selected countries are given in the table below:

The table above indicates that while India still has a very high crude birth-rate, the death-rate stands reduced with the help of improved conditions of living, although the rate of infant mortality is appallingly high. The expectation of life at birth in India is still below 50, while all the advanced country of the world enjoy an expectation well above 60.

As for other countries, the birth as well as the death-rates per 1000 has fallen considerably, not giving any credit to Malthus’ theory relating to population. In India, we can legitimately apply Malthus’ observation that growth in population can go to the extent of food supply only and that, if population grows beyond food supply, a natural check will be applied to population the excess 6f which will tend to get corrected by calamities like epidemics, destruction by natural forces etc.

In Asian countries, Malthus’ observations that unless subsistence levels permit, population growth will bring only misery and ultimate destruction still seem to hold good. Western nations have corrected aberrations in population growth with other means, including a consciousness on their part that social welfare and population growth are inter-connected factors.

In India, too, family welfare programmes are being initiated by the State, and people are being made aware of the fact that social welfare must necessarily depend on lower population growth.

While we refer to ‘crude birth-and death-rates’, it is necessary to clarify the concept for a better understanding. Terms used in demography, that is, the study of population, seek to explain different problems related to it from different angles. Crude birth-rates, or death-rates, are a ratio of recorded live births or deaths in any one year to the total mid-year population, multiplied by 1000.

The crude birth-rate, therefore, is so generalized that it does not reflect the relations of the birth factor to the total population. Persons in different age groups do not account for birth in the same way, and a consideration of the child-bearing age is all important. Hence, in the study of population, demographers lay much stress upon the general ‘fertility rate’.

This rate is determined by working out the ratio of recorded live births in one year to the mid-year population of women in the age group of 15 to 44, multiplied by 1000. The general fertility rate is not the same as the ‘fertility ratio’. This ratio is the number of children below the age of five divided by the number of women in the age group of 15 to 44, multiplied by 1000. This ratio relates the children under 5 years to those that give birth to them, and a picture of fertility rates covering a five-year period can be found out.

Demographers offer a better understanding of the population of a country also by structuring the AGE PYRAMID by indentifying the different age groups in it.

The United States Census of 1970 gives the following picture of the population structure in that country:

The figure shows the exact composition of the population. While children in the age group of 10-12 exceed the 2 million mark for both males and females, those above 55 barely account for a million in each case. The population pyramids are labelled as expansive, constrictive or stationary. The pyramid is expansive when population is the largest at the base and the thinnest at the top.

A stationary pyramid has a more of less uniform structural pattern with a slight tapering at the top to account for a smaller number at the higher age group. The constrictive pyramid has more people in the age group of 20 to 40, relatively less in the age group of 1 to 10, and few at the higher age groups. In other words, it has a fatter middle than either the base or the apex. The U.S. population pyramid is of the expansive type, while the Indian one by and large constrictive in nature.

To what extent geographical conditions influence physique or mentality is more a matter of conjecture than proven fact. Certain generalizations are always sought to be made and no one can totally deny the impact of climate upon human activity. People in hard and dry Punjab are regarded as much more laborious and industrious than those of the lower Ganga valley, whose life is easy-paced and indolent.

McIver observes that besides climatic conditions, other factors like food habits, conditions of hygiene and living standards in general many affect physical as well as mental attributes. Now-a-days, when technology moulds pure physical conditions, these studies will require a re-assessment. In our country, we have learnt to bear the heat and increase efficiency with the help of air-conditioners, and similar equipments have helped Westerners to overcome the crippling effects of severe cold. But this holds good everywhere to a certain extent only.

Some thinkers like criminologists seek to associate physical and other conditions with certain impulses, tendencies and proclivities, and here, too, observation must be taken with great caution. Emile Durkheim tried to show a correlation between climatic factor and the tendency to suicide.

According to him, high temperature raises the tendency to suicide, and there are fewer cases in the colder months of the year. Durkheim even went to the extent of suggesting that suicide rates increase with the rise in the level of civilization and that there were more suicides in the city than in the villages.

For protestants and single or widowed persons there was a higher incidence of suicide than for Roman Catholics and married persons. Suicide would seem to be an impulse when the sense of solidarity created by social conditions is lost and consequently the individual has to rely on his own resources for strength. Whenever such resources are inadequate, the individual decides that the battle is over, and it is futile to knock ones head against a stone wall.

In India, the survey made by the Union Government in 1978 does not establish Durkheim’s theory that suicide is connected with man’s physical environment. According to the survey, there were 42,890 cases of suicides in India in 1975. Incurable or virulent disease accounted for 16.4% of the cases; one percent of the total number of suicides took their lives because of unemployment and 3.7% for reasons of extreme poverty.

Not less than 4,086 persons committed suicide after having quarrels with in-laws. West Bengal alone accounting for 1,009 of this number. In fact West Bengal as a state had the largest number of suicides in that year, and Durkheim’s analysis in no way helps us to account for such a high number in that state, for it is neither the hottest in India, nor the most advanced and industrialized.

The most common means of committing suicide are. in order, taking poison, hanging by the noose, drowning and offering oneself under a moving train. Changing social conditions account for several types of aberrations or complexity in human behaviour and suicide alone cannot be allowed to be explained away merely with the help of the physical environment of man.

The Economic Environment:

The adaptation of the human being to the ecology that obtains for him is based on certain inter-related factors. The population that constitutes the society has a technology and a social organization, and both these factors have to be taken into consideration in order to ascertain the relation between human beings and their environment.

In primitive and undeveloped societies too technology existed in some form or the other, for it can be taken to stand for the means of adapting the human organism to its environment. The primitive community depended on animals and to some extent on plants, for its food, clothing, shelter and even tools. Yet it has been maintained that the concern of the primitive people was mainly for producing food.

Linton holds in the Study of Man that these communities never had a very large number of members, and between 15 to 100 members was the average rule since food could not easily be procured for any number that was higher than that. However, at this stage of human development, technology was at its lowest point.

Technology improved, but still along food gathering lines, when the ‘pre-industrial city’ came into existence. G. Sjoberg uses this term for such towns as held a population of about 2,500 and developed along agricultural lines. While in the primitive community about all were at work with hardly any leisure, with the emergence of the pre-industrial city the concept of division of labour was becoming quite prominent.

Better agricultural techniques became known to the pre-industrial city and, with more of good supply, it could support a larger population. The first point in the division of labour was the distinction noticed now between farmers who worked in the fields and others who engaged themselves in other work. Several new arts were developed, ranging from sewing, weaving, pottery and poultry to these of the goldsmith, the blacksmith and others.

With these new developments, trade increased and made transportation and money-exchange very important and essential; and these were the beginnings of a clear-cut class distinction in society along economic lines. The rich could afford to have the advantages of more of these services and they, thereby, gained more of leisure for themselves. The poor still supplied his necessities to himself, and he built his own house and wore his own cloth.

A logical consequence of the growth of trade and commerce in the pre-industrial city was specialization and a distinct division of labour in the production of goods. Some people were able to secure for themselves the advantages of specialization and the division of labour, and they enjoyed a better standard of living; and occupational differences were also acquiring their respective value differences.

These differences were reflected in the composition and gradation in society. One could easily notice that persons endowed with specific skills and the material advantages associated with them had better dwelling, while the lower class people always lived in the outskirts of the pre-industrial city.

Transportation becoming a very important factor in the economic activity of the community, a well-developed transport system operated by animals was in existence in those days. Not only food, but raw materials too had to be brought from distant places. Food and Water had to be distributed throughout the city, and, by and by, communication becomes a specialized activity. Specialization and larger production of goods made exchange necessary and several exchange centres developed, making commerce a hectic activity in the pre-industrial set-up.

When the ‘Industrial city’ into being in the 19th century in England and then in other parts of the world, the processes of specialization, division of labour, transportation and exchange were further accentuated and perfected into a system of complex economic activities.

There came up the industrial city with mainly extractive work, that is, with mining and smelting operations. Another type of city became the manufacturing centre, while the third type specialized in commercial activities like transportation of raw materials and the exchange of finished products. Whatever the type of industrial city may be, the factor that clearly distinguishes it from the country life or the life of a pre-industrial city is the use by it of the inanimate power in the production of goods.

While in the 1850’s, in the United States human muscle power accounted for not less than 73 percent of work energy, after 1950, 98.5 per cent of work energy came from different inanimate sources, including petroleum and coal. This factor alone has brought about a sharp contrast between what may be described as the ‘rural’ way of life and ‘urban’ life itself.

McIver states that it is difficult to draw a distinction between the urban way and the rural way for, on the one hand, the countryside is changing very fast and not only in suburbs but in far distant villages, too, the impact of the machine is being felt; on the other hand, city life differs even from one locality to another within a short distance, and the heterogenous character of its ways makes urbanism a disparate social way that cannot be put in any specific terms.

Yet the truth is that whenever certain persons are able to exercise control over certain resources that are needed by people in addition to resources for sustenance in life, cities come into existence. In Greek and Roman times, cities developed principally as exchange centres while in India and in China, acquisition of resources by exploitation helped the growth of cities.

Today, mechanization is the principal factor that has helped the growth of cities, enhancing commerce and business activities. Quite naturally, therefore, there is now the attraction of the city that is drawing into it various people from the countryside and that has been described as the ‘pull of the city’.

In India, too, this pull of the city is now being witnessed but, in our country, the factor that explains it is not the mere attraction for city life with it urban advantages. Our country population rushes to the city for employment in different establishments, for the conditions in the villages hardly invite them to a living above the poverty line. With about 80% of our population living in villages, about 45% of the total population lives below the poverty line.

Technological developments have rapidly changed the environment in Western countries and it is estimated that in the span of a century ending with the year 1950, England alone has 70% of the population living in cities.

According to Kingsley Davis, in 1950, 20.9% of the world population lived in cities having a population of 20,000 or more and 13.1% lived in cities having a population of 100,000 or more. He expects that by the year 2000 A.D. one-fourth of the population will live in cities with a population of 100,000 or more; and by 2050 A.D. the cities will draw about half the world population.

In India, according to the definitions used by the Census authorities, ‘urban’ areas are taken to include (a) all places with a municipality or a corporation, cantonment or a notified town area; and (b) all other places with (i) a minimum population of 5,000; (ii) a minimum density of 400 sq km; and (iii) at least 75% of the male population are engaged in non-agricultural activities. While Calcutta has a population of 70, 31,382, Greater Bombay accounts for 59, 70,575, and the population in the Delhi urban area is 36, 47,623.

The following table gives us an idea of urbanization in India:

The break-up of the urban population in some of the states of India is as follows:

When we have a look at the working population in our country, we find that only 32.93% of the total population is in some work or the other, the sex-wise break up being 52.51% of the males and only 11.87% of the females. Of the males, 24.28% are engaged in cultivation work, that occupation drawing the most of the male working (population, while the highest percentage of working women, that is, 5.98% of the total female population in the country, are engaged as agricultural labourers.

Though urbanization has not been a very fast process in our country, India has also been drawn into the pattern of modern economy that has been caused by the industrial revolution,

and a look at the following table will show that we account for not an insignificant share of world production in both the agricultural and the industrial spheres.

According to Walter Goldsmidt, there is a basic ecological process in the growth of cities in relation to improved technology. In the first place, technological developments exploit the environment and help to increase the population-holding capacity of the community. Since total goods available into the population increase in number, movement for sustenance does not become necessary and there is increased sedentariness in daily life.

In the next stage, economic functions based on division of labour emerge as functions distinct from other social functions; and finally, developments in the modern technological economy afford more of leisure to man which helps him in cultivating arts and means of entertainment that are in excess of creature needs of the population. Hollings-Head, however, gives another analysis of the ecological processes in urban centres in his New Outline of the Principle of Sociology.

According to him, factors favourable to man’s economic welfare will bring the population together and the resultant density in a city being the ecological process known as ‘concentration’. The next stage is ‘centralization’ meaning that population coverage on centres that possess high mobility. Meeting places of highways or of land and water transport are important in this respect.

Within the urban community, next comes the tendency to ‘segregation’. This is the process of the city dividing itself into specialized areas. This process, according to some sociologists, follows the theory of the concentric zone or the sector theory of the development of the city. The ‘concentric circle theory’ maintains that settlements grow first around business centres like retail stores, banks, hotels etc.

Residential areas are forced to move away from the centre and, in this process, different circles of areas are found moving outward, the outermost circle moving into the suburbs and having commuters as its population. The ‘sector theory’ similarly divides the city into different sectors, moving outward from the city’s centre, more or less according to occupational divisions. Another theory is that of the ‘multiple nuclei’ which divides the city along similar lines.

The process known as segregation leads to the stage of conflict known as ‘invasion’. It stands for the attempts made by those who belong to segregated areas to move into areas that carry more of prestige and, if the attempts succeed, the last stage in the ecological process that of ‘succession’ follows.

Unprivileged or underprivileged sections of the population may, with the exercise of their personal skill and intelligence, succeed in moving into such areas of the city which carry high rents and are, therefore, considered to be prestigious. Besides those processes, one has also before him the noticeable trend for the suburban life.

The suburb lies on the outskirts of the city and, according to Hollingshead’s analysis; people from the suburbs are very likely to strive for any entry into the city itself. But in countries like the United States, there is a distinct trend for suburban life, not because the suburbanite cannot afford a place in the city, but because he finds the suburb to be a pleasant mixture of the urban advantages and rural freshness.

Behind his decision to stay away from the city probably an understanding of certain factors of urban life works.

It has been pointed out by Richard Dewey (the American Journal of Sociology 1960) that a city life is characterized by the following factors:

(i) Anonymity

(ii) Division of labour

(iii) A distinct feature of heterogeneity in the composition of the urban population

(iv) Impersonal and formally prescribed relationships among urbanites and

(v) Symbols of status which have no connection whatsoever with the person himself.

It has been suggested that the suburbanite wishes to get away from the pressures of anonymity and impersonality of a city; and in a suburb contacts can be more personal and neighbourly feeling grow more easily. Yet they enjoy all the opportunities of city life, and in near city conditions they can live in spacious and family-centred surroundings.

Modern economic activities of man have, therefore, considerably altered his environment. Rural life is based on family sentiments and the semi-isolated pattern of living keeps the villager nearer land. His occupation has a tremendous impact upon his style of living which makes him adhere to simplicity and hard work.

Long established custom and social ethics guide his activities and, through his work of unspecialized nature, he is in closer contact with nature, trying to gain her favour with skill or endure her inclemency with patience. His economic environment is, therefore, unpredictable and over natural forces he has little control. Not being able to secure for himself the advantages of specialized urban living, he has to act in various ways in order to make his living complete. He has to be his own architect, carpenter, gardener, and his wife a cook, a tailor any almost everything else to complete family living.

In a city, customs and traditions as well as family life are affected by several complex factors. Being cut off from nature, life in an urban centre becomes artificial; and lack of simplicity and visible ostentation mark the urbanite’s way of life.

The rural family has such strong bonds that all activities related to occupation, recreation and the practice of religion are influenced by family tradition. Property of the individual is the property of the family, and family opinion in every matter assumes importance. There is so strict social control in a rural family that divorce is very rare.

In a city social contacts are very many, and an individual’s obligations owed to multiple associations make his family ties look rather casual and secondary. Quite a big part of the family obligations is transferred to agencies like the school or the law court, and several of its economic functions evaporate.

The housewife has ready and willing business centres to help her reduce the burden of domestic chores and in that regard the individual’s dependence upon the family is reduced. However, the urbanite’s life is impersonal though there are several social institutions like his educational institution, his office, the play-ground and the club of which he is a member, to the standards of which he will be expected to rise.

The individual has the choice of his occupation in the city and the emphasis on specializationin urban centres affords him ample opportunities for first educating himself according to the needs of his occupation and then specializing in it. Jobs may be unskilled, skilled or of the white collar type and the urban population easily fits into any of them.

Those who have talents find an incentive for improving their performance and an urbanite’s accomplishments would so rate him in the society that he may find for himself a place in the city. Specialization and competition as modes of city life make allowances for social mobility, which means that a person belonging to one stratum of society or the other can afford to rise or fall from such condition according to whether he is able to otherwise.

Another important feature of city life is that women come out of their homes as career girls, and her participation in the harsh, impersonal and competitive world changes her position in society.

Against what can be described as a persistent traditionalism in the country, the city has a sort of associative individualism which allows the individual to feel that he too would matter as a distinct entity rather than as a part of an assortment that is a family. Hence the city dweller does not experience much of the community sentiment that the villager feels. Life is so impersonal in a city that neither does he feel directly attached to his fellows nor is he conscious of his own role via-a-vis his community.

McIver does not think that even cultural pursuits have originated in the city, though the city’s manifold diversions along entertainment and recreational lines are more prominent than those in the country. According to him, all matters of creative imagination originate in the country. The country-side folk songs or the folk dance may be relatively simple, but they are genuine.

The city’s cultural pursuits range from the crude to the highly specialized and the changing moods of the urbanite make these rather temporary and fleeting. Besides that, the villager recreates with the fresh intention of sharing a mode of amusement with members of his community. The urbanite goes for entertainment after hours of tiring work simple ‘to get away from it’. The form of entertainment for the latter is, therefore, pseudo-cultural and, quite often, sick.

One of the principal charges brought against the modern city is that it is drawing the best of the population into it. The city contests the finances of a country and its prestige is high with its many contracts and advantages. Almost everybody likes to share the benefits of city life and, in every country which is industrialized; the majority of the population is urban. Besides that, modern transportation has been able to diffuse urban ways and there is, strictly speaking, nothing that can be described as an undiluted rural way of life.

On the one hand, technological advances have their impact upon rural centres, and the radio, the newspaper and the electric pump used in cultivated fields are now as ‘rural’ as they are ‘urban’ in association. Similarly, as McIver observes, city type organizations are being taken up by rural communities, and such communities no longer remain as isolated as they could have been imagined to be.

Associations or unions of farmers are coming up almost in the same way in which such urban activities express themselves. With so much of interchange of urban and rural ‘culture’, much of the difference between the rural and the urban type is disappearing and hence the charge that the city has the better population is not tenable.

Some sociologists, however, maintain that there is the ‘urban’ type of the individual who is characterized by his emotional and intellectual development, but no study so far has been able to establish that the city-bred is a superior creature is comparison with his counterpart in the country.

Man’s economic environment, particularly with the technological advances, presents yet another controversy for the study of the sociologist. Several scientists are predicting that sooner or later we should be exhausting most of our natural resources required for our industrial development.

The selfish, exploitative character of present economic pursuits is denuding the earth of its wealth and, besides that no economist seems to realize how much of damage we are causing to our ecology. Some sociologists feel that air pollution and exhaustion of resources will affect human life and the growth of the city in a predictable manner. The pollution of water and air, that is so natural a result of industrialization, will poison our surroundings so badly in the near future that with more of industrialization there will be increased pollution along with exhausted resources.

This will lead to a fall in the quality of life and declining population. Then would come a happy turn, for a smaller population would mean less of industrial activity and decreased pollution. Consequently, quality of life will improve and population will increase and a degree of stability would be brought into society.

The entire process as described is expected to take a century and the industrial society viewed as it is from 1900 A.D. would reach the final stabilized condition by 2100 A.D. Capital investment and population will be the highest by 2020 A.D. along with pollution itself, while quality of life will be the lowest in that year.

These sociologists feel that if investments are immediately reduced by at least 40 per cent, birth by 50 per cent and pollution by 50 per cent, the dismal picture of the economic environment can be expected to improve to some extent and a satisfactory future may be envisaged. In 1979, all the countries held discussions on the problems of air and water pollution, and the thoughts about the pattern of city life in future do not now appear to be totally irrelevant.