ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this article we will discuss about Social Groups:- 1. Meaning of Social Groups 2. Need for Study of Social Groups 3. Nature 4. Classification.

Meaning of Social Groups:

Bottomore defines a social group “as an aggregate of individuals in which (i) Definite relations exist between the individuals comprising it, and (ii) Each individual is conscious of the group itself and its symbols.”

In other words, a social group has an organisational aspect (rules, rituals, structure, etc.) and a psychological aspect (consciousness of the members). Thus, a social group is a collection of a number of persons linked together in a system of social relationships with one another.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Maclver and Page, “social relationships involve some degree of reciprocity between those related, some measure of mutual awareness as reflected in the attitudes of the members of the group”. That is, the members interact with one another according to the norms of standards accepted by the group.

Need for Study of Social Groups:

Sociological study of groups is largely a twentieth century phenomenon. During the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth century sociologists were mostly pre-occupied with major trends in societal evolution. Tonnies, Durkheim, Marx, Max Weber and others tried to identify and explain the major historical trends, particularly the impact of industrial revolution on society.

There was, of course, recognition in the writings of a few sociologists about the importance of group ties, C.H. Cooley, for instance, indicated the value of primary group relationship to an individual. However, the fact that individual behaviour is as much a group phenomenon as an individual one was being emphasised from the early twenties.

Since then, this particular aspect has been studied by social scientists from different perspectives according to their respective orientations, such as sociologists, psychologists, psychiatrists and even physicians. As a result, there is now a voluminous literature dealing with social groups.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A study of small groups acquires importance in view of the following considerations. To begin with, social groups, however small in size, deeply affect the society. History is replete with cases which indicate that the decisions of small groups have a critical effect upon the larger society. Revolutionary movements in all countries and at all times were invariably initiated by small groups. Secondly, no man is an isolated island.

The isolated individual who lives all by himself is either a philosopher’s fiction or an abnormal being. In other words, man is a social animal. The sociable nature of man is to be found in the groups which he forms. Human life is essentially group life.

The study of groups is, therefore, of crucial significance in understanding the behaviour of men and women. Any casual observer of human begins will confirm that a group exercises considerable influence on its members, particularly when they arc young.

Moreover, group is a medium through which “we learn culture, we use culture, and change culture”.

Thirdly, “small groups are a special case of the more general type of system, the social system. Not only are they micro-systems, they are essentially microcosms of larger societies…. Through careful examination of these micro-systems, dieoretical models can be constructed and then applied to less accessible societies for further test and modification. Small-group research is thus a means of developing effective ways of thinking about social systems in general”.

The fourth reason for studying small groups is social-psychological. “Because social pressures and pressures from the individual meet in the small group, it is a convenient context in which to observe and to experiment on the inter-play among these pressures. Scientific investigation may lead to general laws about how individuals cope with social realities”.

Nature of Social Groups:

The nature of social groups will be clear if we make a distinction among the following kinds of groups:

Statistical groups are formed by sociologists and statisticians, not by the members themselves. These groups are groups for the purpose of research investigations. Thus, sociologists and statisticians may classify children in terms of age (say, children between the age- group 1—5 years, 5 years 1 month — 10 years, etc.).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These are statistical groups which are significant in so far as these are useful for purposes of investigation into some social phenomenon.

Societal groups differ from statistical groups in one very important characteristic, viz. consciousness of kind. Societal groups include all ethnic groups, all regional groups, all national or state groups, and all occupational groups. Examples are groups of males, females, elderly people, Maharastrians, Tamilians, Bengalees, Assamese, plumbers, etc.

Social groups are characterised by social contact and communication as well as social interaction and social intercourse. Social groups can be of many kinds — friendship or acquaintance groups, neighborhood groups, play groups and many others.

A social group, is also characterised by some as quasi-group or a potential group because it lacks structure or organisation and whose members may be unaware, or less aware, of the existence of the grouping.

Within an organised group there may exist a number of potential or quasi-groups. These groups serve very useful purposes.

“Potential groups are a great source of flexibility and stability. They exert influence at all times because actual groups fear them. It is especially important that they can be activated in support of the rules of fair play…….. We shall not appreciate the full importance of potential group unless we realise that their influence is felt within every actual group. Then we must revise that they cut across many social groups, thus being great latent sources of power In short, ‘potential groups’ are a form of social control latent in every group and in the society as a whole. They remind us of the great importance of the press and other channels by which publicity is given to people’s action”.

An associational group, or, more simply, an association, is an organised group. It satisfies the criteria of social groups and has, in addition, a formal structure or an organisation. Thus, the All-India Railway Workers’ Union is an associational group inasmuch as its members are united together by a similarity of interests.

They are expected to behave in a particular way and conform to or abide by the obligations imposed by the group. Similarly, teachers of secondary schools, say, of Delhi or Bombay do not form a social group (in the strict sense of the term) simply because they have similar characteristics or identical interests. But as soon as they form an Association of Teachers, they form a social group.

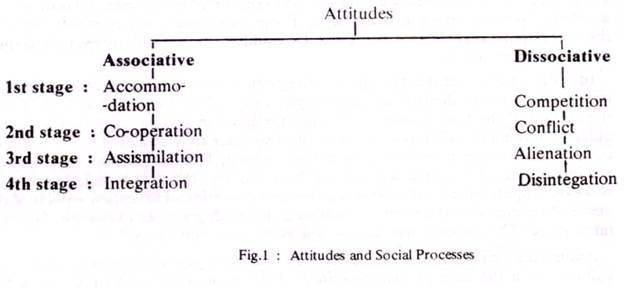

Classification of Social Groups:

The variety and diversity of human groups defy all attempts at categorisation. Groups can be considered in terms of their major interests — as in the case of religious groups, political groups, etc. — and, then, these may further be sub-divided on the basis of sects, cults, etc.

In the case of religious groups or on the basis of pressure groups, interest groups, etc. In the case of political groups. Groups may be considered in terms of their organisational structure as well. Thus, we speak of democratic group, totalitarian group, etc.

Groups may also be considered in terms of the socio-economic class to which the members may belong — as in the case of industrial groups, agrarian groups, etc. In this way innumerable illustrations may be given in order to show that any conceivable criterion may be made the basis of classification of groups.

It is, therefore, not possible to consider all types of groups. We shall, therefore, consider only those social groups which are regarded as the most general and most widely acceptable.

We may first take up the classification given by Cooley, Angell and Carr who arranged, in order of increasing size and decreasing intimacy, social groups into four general classes:

1. Primary Group:

The concept of the primary group was introduced by C.H. Cooley. By primary groups he meant the intimate, personal, ‘face-to-face’ groups. For example, our companions and comrades, the members of our family and our daily associates may come under this category.

The expression ‘face-to-face’ should be interpreted figuratively, not literally. It is possible to have face-to-face relations with people who are not members of our primary groups. Likewise, it is possible that we may not have face-to-face relations with those who are members of our primary groups.

For example, we may have face-to- face relations with our barbers or laundrymen. There may not, however, be intimacy or primary-group relations with them, even though we see them face to face. On the other hand, we may correspond regularly with our close friends whom we may not have seen for many years.

It is the degree of intimacy, or social distance, rather than physical distance that determines the primary group. Relationships among primary group members are based on personal intimacy, and not on contractual obligations. These relationships are often long-lasting.

These intimate and closely-knit groups are primary in different senses:

First, face-to- face group is the nucleus of all social organisations — “it is the unit cell of the social structure”, Maclver and Page have described it can be found in all societies.

Secondly, an intimate groups provides the most significant social and psychological experience for its members.

Thus, the primary group in the form of the family helps a child to acquire within the confines of a small group his personality as well as “his earliest and completest sense of social unity”. It is through such groups that we, as play mates and friends, give expression to our social impulses.

These primary groups can be characterised as informal. These informal relationships emerge from frequent interaction among members who come together freely and spontaneously, as is illustrated by the play group, the study group or a group of friends. Though the members of these groups may not develop any formal organisation, they assign, more or less spontaneously, different statuses and roles for each of them.

When a group of children regularly play together or when a group of friends frequently meet, they grow a sense of common identity, and share common values and obligations, though they may not be aware of these things. The primary groups emerge whenever and wherever a group of people meet more or less regularly and interact with one another.

It will, however, be wrong to assume that primary groups are found only in social groups of the nature of the family, the play group, the group of friends, etc. They appear even in the midst of very highly organised and complex groups: in college dormitories, in factories and offices, in the army and in prisons. We find in these groups both a formal blue-print arrangement and informal face-to-face groupings.

In a college hostel, for instance, there are formal rules and regulations that guide the conduct and mutual relationships among the borders. But there emerges a number of friendship groups or interest groups which have the qualities of both spontaneity and intimacy. The borers derive psychological satisfaction in and through such informal groupings.

The presence of such informal groups in factories influences, to a considerable extent, the morale of the workers, their productive efficiency and industrial relations in general. This explains the growth and development of the field of ‘industrial sociology’.

Those who have done research on inter-personal relationships in the army, the prisons, the office or the factory have discovered the existence of primary groupings in these formal establishments also.

Importance of Primary Group:

Primary group relationships are equally important to both the young and the adult. A child, for instance, experiences social living for the first time in and through the family and the peer group.

These groups are characterised by intimacy and spontaneity and, as such, the child learns many things concerning social life—the basic values, the prescriptive and proscriptive aspect of social norms—almost effortlessly from these groups.

Since relationships in such groups are marked by love, affection and mutual trust and understanding, communication from the one to the other is easy. In course of time, a child integrates the values and ideals of society in his personality. In the absence of primary group relationships at an early age, indoctrination into the ethos of society would have been a very difficult process.

Secondly, primary group relationships are equally important for the adults. This aspect was discovered accidentally. During and immediately after the Second World War the number of mental patients in the U.S.A. far outnumbered the availability of psychiatrists in that country.

In the circumstances, the patients could not be attended to singly. The only alternative left was to keep a group of patients under one psychiatrist. The outcome of this arrangement was unexpected. The patients responded to treatment much more quickly and much better than they used to be treated singly under a psychiatrist.

Such miraculous improvement was attributed to the fact’ that the primary group relationships which developed among patients in course of their treatment provided the required psychological support and confidence. This discovery led to a new line of treatment called ‘primary group therapy’ in general hospitals also.

The results of this experiment have been equally encouraging. Being encourage by such success, some of the Western countries introduced the ‘group approach’ in reforming and rehabilitating the convicts housed in prisons. In the U.S.A. this group approach is being widely used in tackling cases of juvenile delinquency.

A new line of professional approach called ‘Social Group Work’ has consequently emerged in social work field. The importance, of primary groups in tackling cases of mental, physical and social illness cannot, therefore, be over emphasised.

Thirdly, research investigations have revealed that the task of maintaining discipline, punctuality and morale among workers in large establishments yields better results if one proceeds through numerous primary groups which develop spontaneously among them. The techniques of primary group approach in these fields constitute the subject matter of a new branch of sociology called Industrial Sociology.

It will be appropriate to refer to a paradox. On the one hand, we are increasingly becoming aware of the important role that primary groups play in the complex society of ours. There is, on the other hand, disappearance at a pretty fast rate of the conditions that are favourable for the growth of primary groups. The improved transportation has increased the pace and range of physical mobility.

As a consequence, neighbourhood is fast disappearing. The bonds of intimacy among neighbours and kins are, naturally, getting weakened in the changed circumstances. Moreover, life has become complex and the needs of people varied and multifarious.

Different types of associations, therefore, needs must grow in order to cater to the myriad demands of people. In other words, life tends to become more associational and increasingly less communal in nature.

2. Secondary Group:

In the changed circumstances, we develop, in contrast to the intimacy and spontaneity of primary groups, formal organisations described as secondary groups (this term was not introduced by Cooley) in which the individuals have functionally defined roles as members of the group.

Personal intimacy and face-to-face relationships are altogether absent in these secondary groups. We may consider, for instance, the case of “big” colleges in which the student population is so large that teacher-student relationships are not based on personal acquaintance, but on specialised group roles.

Students are, in most cases, known to teachers by their roll numbers, and teachers are generally known to students by their initials.

Today an increasing number of our relationships are secondary. One reason is that our contacts have grown in number and variety as a result of improvements in means of communication and transport.

We may find another reason in the complexities of modern social life which require accomplishments of a large number of tasks through formal, bureaucratized, large-scale organisations, as in the case of wide-spread network of health services. Many other essential services are provided by similar large-scale organisations. All these have naturally led us to develop a number of secondary ties.

The decline of the primary group and the corresponding increase of secondary groups have one very immediate consequence. Because of the nature of secondary groups we are now associating more as mere functionaries and less as whole persons. In primary groups people meet as persons with no limitations of artificiality, special purpose, and the like.

In secondary groups, on the other hand, they are functioning units in an organisation, or mere acquaintances at best Secondary groups may, therefore, be called partial associations. This means that under such conditions associating persons “present only special facets of themselves to one another”.

They do not meet as whole persons, as in primary groups. In big colleges, students listen to formal lectures from professors, and they have no conception of what the individual professors are like as persons than the professors have of what the individual students are like as persons.

Similarly, as consumers we buy our household necessities from individuals who leave their impact upon us merely as functionaries, never as whole personalities.

3. In-group and Out-group:

The groups with which an individual identifies himself completely are his in-groups. He has feelings of attachment, sympathy and affection towards the members of these groups. He uses the word ‘we’ with reference to these groups. Family is a familiar example of in-group for most of the individuals.

An out-group, on the other hand, is defined by an individual with reference to his in-group. He uses the word ‘they’ or ‘other’ with reference to his out-groups. The relationship of an individual to his out-group is marked by a sense of remoteness or detachment and sometimes even of hostility.

It is obvious that in-groups and out-group are not actual groups except in so far as people create them in their use of the pronouns ‘we’ and ‘they’ and develop a kind of attitude towards these groups. The distinction is nevertheless an important formal distinction because it enables us to construct two significant sociological principles.

The first of these principles is that in-group members tend to stereotype those who are in the out-group. Thus, the north Indians have stereotypes of those who live in the south.

As a matter of fact, those who live south of the Vindhyas are lumped together by many northerners and given a stereotype, ignoring completely that those who live should of the Vindhyas are dissimilar in many respects, in terms of dress, food, language, etc.

The southerners likewise have their own stereotypes of the northerners which do not take into account the variations among northerners. The significant thing is that such stereotypes are usually formed by considering only what appears to the members of the in-group the least respectable traits to be found in the character of the members of the out-group.

Another significant thing is that “we tend to react to in-group members as individuals, to those in the out-group as members of a class or category. We tend to notice the differences between those who are in our in-groups and to notice only the similarities of those in the out- group”.

The people of each linguistic state in India have a tendency to form stereotypes of the people of other linguistic states. A Punjabi, for instance, has a stereotype or a generalized perception of what Bengalee stands for and how he behaves, completely ignoring the fact that all Bengalees do not fit in with that stereotype.

Those Punjabis who have lived with Bengalee families for a fairly long period of time know from their experience that all Bengalees are not similar and that stereotypes are based on wrong perceptions. In fact, social distance encourages such categorization and discourages individual differentiation.

Knowledge of this principle helps considerably to reduce the unfortunate effects of such categorization into stereotypes and to demolish the barriers that obstruct the easy communication and intercourse between people and people.

The second principle that is deduced from the in-group—out-group distinction is that any threat—real or imaginary—from an out-group tends to bind the members of the in- group against the members of the out-group. This may be illustrated with reference to our experience in family situations.

Mencius, the Chinese sage, said many years ago:

“Brothers who may quarrel within the walls of their home, will bind themselves together to drive away any intruder”.

Likewise, when any criticism emanates from the members of the in-group, it is not only tolerated but its assessment is sought to be made in a cool and dispassionate manner.

When, however, similar criticism comes from the members of the out-group it is resented and hotly contested, sometimes in an unjustified manner. This is an important principle which should be kept in view while offering any suggestions for reform or improvement of a condition which concerns the members of an out-group.

4. Reference Group:

The concept of reference group was first developed by Hayman. Subsequently, Turner, R.K. Merton and Sheriff elaborated it further. The concept of reference group, as originally developed, may be explained thus: In some situations we conform not to the norms of the groups to which we actually belong but rather to those of the groups to which we should like to belong, those with which we would like to be identified.

A reference group may not be an actual group. It may even be an imaginary one. Any group is a reference group for someone if his conception of it, which may or may not be realistic, is part of his frame of reference for assessment of himself or of his situation.

Thus, an individual who is anxious to move up the social ladder usually has tendency to conform to the norms of etiquette and speech of a higher social class than his own because he seeks identification with this class.

By way of illustration, we may refer to the concept of ‘sanskritisation’ enunciated by Srinivas.

“Sanskritisation is the process by which a ‘low’ Hindu caste, or tribal or other group, changes its customs, ritual, ideology, and way of life in the direction of a high, and frequently, twice-born caste. Generally such changes are followed by a claim to a higher position in the caste hierarchy than that traditionally conceded to the claimant caste by the local community. The claim is usually made over a period of time, in fact, a generation or two, before the ‘arrival’ is conceded”.

The concept of reference group is sometimes given a wider meaning in that it calls attention to the fact that groups to which one does not belong and cannot belong or with which one does not want to identify also serve as reference groups.

For members of a particular group, another group is a reference group if any of the following circumstances prevail:

(1) When members of the first group aspire to membership in the second group, the second group serves as the reference group of the first.

(2) When members of the first group strive to be like the members of the second group in some respect, the second group serves as the reference group of the first. It is to be noted here that the first group wants to be like the second group simply because the first group cannot secure the membership of the second group.

For example, the non- Brahmins in some parts of India have a tendency to emulate the ways of behaviour of the Brahmins (compare the concept of sanskritisation) in order to acquire the prestige of the Brahmins.

(3) When the members of the first group derive some satisfaction from being unlike the members of the second group in some respect, and even strive to maintain the difference between themselves and the members of the second group, the latter group is the reference group of the first.

For example in the U.S.A. the whites strive to remain unlike the Negroes. The satisfaction of some white Americans in just being ‘white’ is possible only with reference to the ‘non-white’ group.

Further, the status of being a ‘white’ is not simply a matter of possessing ‘white’ skin. It also involves, in terms of prestige, superiority in ranking and enjoyment of privileges. It is, therefore, not unlikely that the ‘whites’ could lose their superior status without losing their white skin. The whiles, therefore, strive to distinguish themselves from Negroes by retaining privileges.

(4) When, without necessarily striving to be like or unlike or to belong to the second group, the members of the first group appraise their own group or themselves by using the second group or its members as a standard for comparison, the second group becomes the reference group of the first.

For example, in some situations the non- teaching employees of colleges are found to assess their own performance or record of attendance with reference to those of the teachers.

5. Voluntary Groups and Involuntary Groups:

The distinction between voluntary and involuntary groups corresponds exactly with that made between achieved and ascribed statuses. There are some groups we join on our own. These are voluntary groups of which we choose to become members.

For example, one becomes a member of a literary group, not because one has to but because one decides to seek the membership of the group to pursue one’s literary interests.

There are, however, some groups of which we are members because we have to. We have no choice in the matter .These are involuntary groups. One becomes, for instance, a member of a caste group simply because he is born into that particular caste. Similarly, one is a Tamilian, a Gujarati, an Assamese or a Bengalee because one is born of parents who belong to that particular linguistic group.

6. Large Group and Small Group:

Groups may also be classified on the basis of the number of members composing the group. A large groups is obviously a group comprising a large number of members and small group a group of limited number of members.

Strictly on the basis of the strength of membership, a group is generally classified into categories. The first is called a dyad or a group consisting of a pair- mother and child, a married couple, a partnership of two, etc. A dyad grows around mutual love and similarity of interests or predilections of the pair, and hence it may break up as soon as the motive force bringing the pair together disappears.

The second is called a triad or a group comprising three persons.

The significance of a triad is brought out by Simmel thus:

“in groups of three, the third person ‘may act as a mediator, as a holder of the balance of power, or as a divider who creates conflicts that destroy any sense of unity between any two of the persons”.

The third is a group comprising more than three persons. This kind of group is further sub-divided into large and small depending on the number of persons who comprise the group.

7. Patterned and Non-Patterned Group:

There are groups which are organised on a hierarchical principle. Thus when a football team participates in a competition, the team consists of, besides the players themselves, a team manager, a coach and a captain chosen from among the players, All of them are assigned very specific roles and the relationship among them is also governed by specific norms.

Such a group is called a patterned group. There are numerous groups of this category in every society. A group which is designed to achieve some goal needs must be patterned.

There are, again, some groups which are organised informally, the members having no specific role obligations. On the contrary, they enjoy a considerable amount of freedom within the confines of a very broad framework. There is generally no hierarchy.

Such a group is called an informal or a non-patterned group. This type of group allows a considerable amount of flexibility to its members and, as such, is most suited in situations which call for creativity, and innovation from its members.