ADVERTISEMENTS:

The following are the agencies of social control in India:

(I) Custom, (II) Folkways and Folkmores, (III) Law, (IV) Religion and (V) Education.

I. Custom:

Custom denotes habit not in the sense an individual acquires a habit. It is a social habit in the sense that once the members of a group form a habit, it becomes a recognized custom only if it is backed by social sanctions. While Ginsberg states that custom gets so ingrained in life that we follow it almost instinctively, McIver and Page stress the inter-relationship of habit and custom.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An individual habit like taking tea or coffee with morning breakfast is not a custom; when a habit becomes socially expressed and when it carries social and external sanction, it becomes a custom. For example, holding celebrations and festivals are a custom but having a get-together of friends on holidays is a habit.

It is important that a particular mode of behaviour should be adopted as a practice by a social group before it is regarded as a custom. Going to church on Sundays is a custom among Christians, while saying prayers individually at some times of the day may be a habit if done voluntarily.

Again it is a customary principle for married Hindu girls to wear the vermilion mark on the forehead, and there are sanctions for the neglect of the duty, but a peculiar style of wearing the sari is a matter of habit. Sex taboos are customary rules, but preferences in the matter are a matter of habit.

It is true then that habit is more of an individual factor, while custom is connected with social relations, and, therefore, if an individual does not live in a society, custom has no value for him. From a certain point of view, it may be said that custom generates individual habits; if taking tea at 4 p.m. is a custom among English people, every Englishman is expected to take tea at that time.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Customary rules play upon the individual from childhood and different habits grow; but at times, with new invention and technological advancements new habits may be acquired, and these habits in turn may formulate new customary rules. When the newspaper was first introduced among the Indian urbanite, some formed the habit of reading the papers in the morning; today, the morning newspaper is a socially accepted matter, and going through it is practically a custom.

Again, another distinction between a habit and custom is that individual habits usually do not carry any sanction as long as they do not come into conflict with social norms. No one is despised by society if he has I additional cups of tea, besides the customary afternoon refreshments.

But if it is found that a particular family does not observe the custom of having the afternoon tea, it will be placed under social ridicule. Social pressure is exerted in matters of custom and the one who does not conform to custom will either be despised or gradually be placed under conditions of ostracism. The element of social pressure, however, must not be exaggerated for, it is claimed by sociologists, that if customary rules were merely dependent upon social coercion and they were not in themselves beneficent to society, they would not have been able to stand the test of time.

If an individual voluntarily conforms to custom, he comes into no conflict with society and its norms. If, on the other hand, if he places individual interest above group interest and gives precedence to his individual habits rather than to customary laws, society comes forward with its pressures upon the individual, who may either learn to conform to social norms or revolt against them and, perhaps, become a deviant or a delinquent.

Rousseau over-emphasized the element of social pressure by looking upon it as a means of tyrannizing over individuals or, at least, as the device of the society to secure the surrender of the individual to its ways.

Even McDougall, the social psychologist, observes that custom creates a complexity of rules and regulations for holding different elements in society together and to make them adhere to its norms and standards; at the same time, it has liquidated and destroyed the rebels against such norms and standards.

What custom establishes with permanence, ‘fashion’ modifies with varieties and as such, custom becomes more enduring than fashion; it has a closer relationship with life and the traditional qualities and values of society.

‘Law’ is a specific code and it is more organized than custom. Custom itself cannot be regarded as law as we understand it today, although several customary obligations have been translated into legal provisions by the legislature of different countries. Custom is more spontaneous in its origin and its sanctions are also more immediate and more formal than those of law.

In making a comparative study of law and custom, it will be imperative to consider certain factors that regulate the relation between the two. It is true that in modern societies, customary principles which had all along been effective in regulating actions of simple men are fast becoming inadequate, and law must complement customary rules.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

First of all, in the matter of inter-relationship of the two, it will be noted that custom is voluntarily accepted by society and legal codes are evolved through much deliberation. The social subject almost unconsciously responds to custom but our responses to legal codes are conscious and compulsive.

Secondly, a specialized agency with powers of authoritative jurisdiction is required for enforcing the law and such agency is usually located in the judiciary; for enforcing custom, no such agency is required.

While an elaborate machinery consisting of the police personnel, officials and the law courts looks after law and its violation, social interactions produce the desired effect of bringing the offender of customary regulations to book. Whenever State power is well organized, an arbiter is required for pronouncing the law and its fine interpretations.

The judge when he delivers his judgment may, in fact, clarify the position of custom and make a new law. After all, constitutional provisions to a great extent provide recognition to customs and conventions and convert them into the law of the land. When we say in our country that the President is immune from the law, who does not recognize in the principle the restatement of the customary rule as to the Divine Rights of Kings and the King’s prerogatives?

Thirdly, in a complex society, it may be found that customs regulating the different ethnic groups differ from each other in a vast measure and, in such cases; the law is required to harmonize State and national activities by operating as a single agency for providing the people with codes.

This task is not very easy of performance; and, in India, a clear distinction is made between constitutional, proprietary and personal rights. While constitutional and proprietary rights are made uniform, personal rights and obligations still remain to some extent within the ambit of custom.

Therefore, Hindu personal laws as to marriage guardianship and succession are not the same as the corresponding laws that apply to Muslims in the country. In totalitarian countries, all such differences have been wiped off arbitrarily and with the use of the strong State machinery. Fourthly, custom appears to be more enduring than the law in the sense that few modifications are made to it; and if modifications were needed so urgently, the rules would not have been regarded as custom in any way.

Law is alterable and, with the rise of new and complex situations, laws are adapted to the need of the hour. In times of peace and normalcy, our constitution allows us several freedoms; but in times of grave emergency like external aggression upon the country, many of these freedoms can be curtailed by enacting different laws to that effect. Similarly, economic control has been found to be legally necessary from time to time in order to prevent abuse of the processes of a free economy.

Custom is more enduring, possessing a built-in device for adapting itself to varying conditions. Customary principles come down through centuries of experimentation and they are usually regarded as beneficial to the group as a whole. Since, they aim at general welfare, and not at the advancement of certain specific interests in the society, they suit all circumstances and do not require modifications.

When, however, they are found to be based on age-old blind beliefs and superstitions, education ensures their obliteration; and one may even venture to state that the process of their liquidation in such circumstances begins even before formal education establishes their emptiness.

Lastly, another factor distinguishes custom from law and that relates to the quality that man possesses in addition to, and by way of distinction from, the faculties possessed by animals: It is his rationality. Everything that the human being concerned which is not external behaviour and material interests; he has his mind and the intellect that is concerned with matters like faith, creed and ideologies, may argue that creeds and beliefs are mental conditions that appear as products of the interplay of custom upon individual, family and group lives.

Whatever it may be no law is effective if it ever comes into conflict with group creeds and beliefs. We know how disastrous it would be to coerce an average Indian into believing in the non-existence of God. Call it custom, or term it as superstition or blind faith, he has been reared in the midst of staunch religious beliefs; his very soul smacks of religious attitude.

The law in this matter becomes a very delicate affair, for every docile Indian has for ages and even under foreign rule remained alert lest his religious beliefs are trampled upon. In matters of creeds, faiths and ideologies, therefore, the law cannot take an authoritative posture.

II. Folkways and Folkmores:

According to Sumner, man has obtained from his ancestors certain proclivities, skills and habits by way of heritage, which enable him to solve several of his problems, like those relating to production of food or food habits, sex relationships I and his aesthetic sensibilities. These become the ‘folkways’ of his society for, in formation of these unwritten rules, deliberation by exchange of thoughts between different elements of the society took a very important role.

If several individuals have to live together, particularly in geographical proximity, they have to come to an understanding as to their common way of life which helps in co-operation between them. Almost all in the society voluntarily follow the rules formulated by such understanding and much upon their willingness to follow these folk-ways depend upon the organization and the stability of such society.

Sumner asserts that folkways are none other than ‘social habits’ that ancestors pass down the generations, and posterity finds them acceptable to their way of life. For example, nobody in our country objects to the practice of folding palms when a guest or an acquaintance is being greeted; in the West, the manner of greeting is a wish, with or without a handshake.

In certain parts of Central and West Asia, people rub noses to show the warmth of their feelings. While the Indian married woman puts the vermilion mark on her forehead, her Western counterpart carries her status on her ring finger. It is interesting to note that the folkways of a society are usually not followed by another, except when a transfusion of cultures has taken place; and, in fact, at times the ways of a community or a society may be despised by another.

For example, some Europeans kiss each other, irrespective of sex or station in life, when they exchange greetings; in India, an average man would consider the practice as an act of vulgarity. When an Indian touches the feet of an elder to show his respects, the European might find it to be a weird and servile practice.

It cannot be maintained that folkways are products of such deliberations as guarantee the secure findings of rational exercises of judgment. At times, no judgment of the intellect is involved in the practice; but a process of trial and error must have obtained before the practices came to be generally accepted, particularly with regard to food habits and attires, definite experimentation seems to have been the basis of crystallization of practices.

Food habits in dry climates appear to be different from those in moist ones, and the people living in hot parts of the world can of consume the food that is taken in the colder regions. Milk, taken hot in India, is referred cold in Europe.

Similarly, the Westerner might consider the Indian mode f dress as bizarre, but the excessive heat of the tropical region does not allow an average Indian to be bedecked with debonair European coverings for most parts of the year. Attitudes of hospitality and tolerance for others’ thoughts must have developed after it was found that constant and unrelenting hostility towards neighbours and strangers was futile.

Folkways are inculcated in the individual through suggestion and indoctrination and the processes are so natural and spontaneous that no individual thinks of revolting against them. There is no definite authority for punishing an individual who would not follow the folkways, but every person is invested with knowledge that the collective opinion of the society will go against him if he seeks to violate any of these.

There is ridicule or contempt for him in case he makes any violations, and not many heads are strong enough to bear the pressure of social ridicule, which may even take the shape of virtual ostracism. The attire for girls is different from that which boys must adhere to, and a boy who shows a liking for girl’s clothes is so ridiculed by society and shunned by his fellows that he prefers correcting himself rather than remaining a rebel.

It, therefore, follows that the chief merit of folkways lies in their being accepted as valuable guidance to the way of living. The sound of the tongue touching the palate when one takes his food is regarded as so objectionable by cultured society that a person who seeks advancement in his life would not dare to continue with his own inadequate standards.

Obedience to folkways is almost a built-in mechanism in social man, and he does not look for any authority who would punish him for his lapses. The adventurist is always there, but no exception has ever been strong enough to disprove the rule. If a man decides to be rough in the presence of ladies, he may not interfere with legal provisions but he would come perilously near to being an outcast.

Informal codes written large in contempt, ridicule or a sneer act as a direct social control and persons believing in social relationships must of necessity seek to avoid such degradation caused by the violation of folkways. It may appear, however, that no one in society is truly bothered as to observance or otherwise of folkways; and particularly in the case of city life, no individual may find the scope for meticulously following these ways and nobody may even notice his minor lapses; the case, of course, would be different in villages where relations are more of a primary nature.

As it is true that with a habituated or an indoctrinated mind, a social individual builds up his relationships with a clear understanding of folkways so, it is an accepted fact that folkways that have crystallized through practices for long periods harmonize social relationships and act as an unwritten agency of social control over individuals. Perhaps because it is known that few would be willing to violate the rules that are principally aimed at making social intercourse aesthetic, the penalties for their violations are light.

‘Folkmores’ are such habits and practices as are concerned not merely with group welfare gauged according to principles of aesthetics, but are distinctly connected with values and value judgments. When folkways were formulated, mere convenience might have been the deciding factor and whether a man should or should not stand up to show his respects to elders and ladies could have no element of right are wrong in the question.

But sooner or later, the sense of good and bad and right are wrong dawned upon the members of society so that they appreciated the evil effect of violation of certain principles. Practices based on these principles came to known as folkmores and one can describe them as ‘folkways that have taken the compulsive form’.

Sumner states that ways of life that have been determined by distinct value] judgments come to be known as folkmores. The mores decide upon questions ethics and not merely upon suitability of behaviour, and also upon questions propriety. The questions of propriety add value to mores and the authority that enforces the mores also tends to become more distinct in nature.

A sneer, a look of ridicule or words that derogate an individual from his usual position may be natural correctives to loose behaviour that goes against folkways; but mores are considered f to be essential to the very existence and stability of a society.

In the days when tribal clan or family authority was considered to be supreme, undue closeness with an alien was taken to be disruptive of group harmony; and from that feeling came the idea that exogamy could promote acts and thoughts of treachery. Exogamy became prohibited and punishable and so was the inclination in favour of any foreign culture. The mores gradually took note of the undesirability of sex relations among siblings and incest became a taboo with severe penalties.

The mores cover different spheres of life and different standards can be taken to be obtained in different societies. For example, the Indian society is very rigid about romantic love and premarital sex; mores in this respect are somewhat harsh. The widow’s austere mode of life is a strict more in Hindu society, stricter in a way than the mode of life prescribed for the mendicant.

The different strata of society have mores that differ in application and severity. In feudal times, it was not a misdemeanour for a peer or a zamindar to have unwedded sex partners and, even today, the practice of living together is not reprehensible among the lower classes. Neither ostracism nor retributions will threaten the existence of the individual indulging in the act.

But consider the case for the member of the middle class, and the mood of appreciation changes. As Bernard Shaw puts it, middle class morality prohibits activities that may be customary with other classes. Changing times, too, can have a modifying influence upon the mores.

The position of the widow in India has been bettered after the model of Western liberal and humanistic thinking, and the study of the social sciences accepts a romantic longing of one young person for another as an expression of a very natural impulse which cannot, and should not carry value judgments.

The environment and the group to which an individual belongs can also determine the nature of the more that is to apply to him. The city dweller may wink at some of the prominent mores like those related to adultery or inter-caste marriages, as in India; but the villager is still under strict surveillance in this regard, and village heads and panchayats bring their axes down upon every lapse that deserves punishment.

The punishing authority may, according to circumstances, be the head of the family, the high priest the village panchayat or the head of the locality concerned; the authority is at least more distinct than the one that regulates folkways. The nature of the penalty is harsher in the case of the mores than for the folkways, varying from physical torture to ostracism.

These penalties are not prescribed by the law of the country, but the penalties all the same remain effective. Any person violating the sex mores may be beaten up, made to starve for a few days or even paraded down the village, being mounted on an ass and his head shaven. Fear of any of these may operate as a check upon an individual’s behaviour and, when we consider that many women in our country have been thrown open to immoral traffic for violation of mores, we may assert that women fear lapses from mores in a greater measure than men.

Mores tend to become less effective if geographical mobility is high in any group or community. On the one hand, occupational demands can make a person shift from his usual surroundings and seek shelter in the wider complex of an urban life; on the other, if mores appear to be oppressive and unreasonable, as is the case with social bans upon inter-caste and inter-provincial marriages in our country, one may take the advantage of the more liberal law of the country and dissociate himself from his family or group.

A Brahmin youth can live in comfort outside his native village even though he has married a girl belonging to the Scheduled Caste or tribe; he will feel all the more secure because the enlightened statutory law will grant him protection. Therefore, one may conclude by saying that mores will be obeyed and respected as long as the collective social intellect considers them to be trustworthy and benevolent for social stability and development.

As soon as it is realized that they are a hindrance to individual development, every individual would be faced with a choice as to whether it is advisable to continue with the restrictions or it would be enlightened behaviour to discard the old, age-ridden practice that no longer carries weight and conviction. In changing India, an average youth is faced with this choice and this is one of the factors that indicate the generation gap between him and his orthodox elders.

III. Law:

Law as an agency of social control is a much later development than custom, folkways or folkmores; it is more recent and more liberal than religious precepts. Law may take the shape of unwritten conventions or codified commands made by a recognized authority and, in either case, there must be a well-defined machinery for enforcing the provisions.

Ehrlich builds up a theory that law depends on the condition of acceptance by a group which itself creates the legal complex that is to apply to it; the judge makes it more precise in his judgment so that the living law that the community observes fixes the norms that it must attain to. The sociologist R. Pound (in his Sociology of Law and Sociological Jurisprudence) observes that living law as the community observes may not be the same as the code that is stored in official files; and that the real law does not consist of propositions but of legal institutions created by the groups within a society.

The sociologist therefore studies the law, on the one hand, with an understanding that every living hand rests on the consent of the group or the community to which it applies and, on the other, with his attention riveted more upon the processes that make the law and institutions that support them rather than upon the mere provisions themselves.

The basis of law, as understood in sociology, is the relation between human behaviour and disorder. In order to know how law operates, it will be necessary to understand the factors that cause changes in any society and govern its evolution. In any legal system, the knowledge of the social interests becomes necessary when we take into account the fact that man’s ideas about ethics and matters relating to his creature needs and social needs have not remained the same throughout the ages.

With a change in his views, the legal provisions have changed and the evolution of law can well be said to have been connected with changing social interests. With technology and innovations affecting our life modes, our interests have changed; and laws have correspondingly been subjected to a process of alteration and adaptation by comparing the application of the theoretical bases of law with the’ practical results that have been obtained.

Law can then be looked upon as a function of society rather than a mere abstract set of rules, and even the courts now- a-days very often test the social policy that lie behind certain rules of law rather than confine themselves to mere arguments of abstract logic. This is known as the functional approach to the study of law, and this approach satisfies the sociologists, whose task it is not only to study social facts but also to prescribe standards that are to be attained.

While in primitive societies customary principles were effective enough for controlling human behaviour and aberrations, the need for something formal and coercive arose and along with that need came the urgency for a lawyer and a law- administrator. The concept of the welfare state as is current now-a-days imposes heavy duties upon the State not only in the negative aspect of control in preventing undesirable action, but also in its positive aspect of prescribing affirmative norms to which a healthy and a right thinking individual must conform.

Although coercion is a weapon in the hands of the State when it fixes the law for its nationals, force alone cannot uphold the sanctity of the law. As already observed, such laws are likely to survive the test of time as are considered to be right and ethical; legislation that is unethical or immoral will be rejected particularly in an open and participating society. To this extent, a link can be observed between morality and law; and to this very extent also, law and custom can be said to be related, for whatever is established custom today may tomorrow find its place in the statute books.

But while custom tends to remain static, law is marked by its dynamism. The question whether or not law is functioning as an effective agency of social control can be determined by examining the relation between law and society, that is, the factors that shape the correlation between the two.

Almost every modern nation being closely identified with the State it represents, the State is required in each case to show a greater understanding of the needs of the society and the spheres in which the State power can introduce its legal mandate. For the study of this correlation, in the first instance, it is necessary to distinguish between the ‘simple society’ and the ‘complex society’.

A simple society is the one based on the single principle of kinship, class or the tribe. Such a society has evolved from the mere fact that in conditions of geographical contiguity, certain persons related by blood, or others related through the common bond of occupation for subsistence, have grouped together. These are more or less closed and self-contained units which have not faced any outside, disruptive influence.

The complex society, on the other hand, as shown in the patterns of the more modern nations and states, has grown out of the interplay of multifarious factors, the ethnic with the linguistic, the spiritual with the temporal and the economic with the political or the geographical. Every complex society must, in the past, have begun along simple lines, but the times of their origin in simplicity are almost forgotten.

The relation between the laws and the society can well be understood by considering the accommodation in each society of the following factors:

(1) Law-Making Authority:

In simple societies, laws are observed as an heritage, and the entire tribe or clan may itself be regarded as the law-making authority though, at times, some sort of imposition of the law, more by the spiritual authority than by the temporal one, may be envisaged.

The complex society has, virtually without any exception, a well-organized body of legislators who must be well qualified for the job, according to the law of the land, for example, members of the legislative body. In the majority of the complex societies, they are elected by the people of the State, while in some monarchies the legislators are nominated by the sovereign himself.

(2) Law-Enforcing Authority:

In simple societies, any violation of law may be enforced by the chief or the head of the tribe or the clan; by the paterfamilias in case of kinships, or by the spiritual chief, including the head priest or the witch doctor. In complex societies, a distinct organ of the government under the name of the judiciary enforces the law.

The members of the judiciary are required to possess specialized qualifications and experience, and be persons of unimpeachable integrity. Though in some countries judges are elected, in most cases they are rarely made directly responsible to the electorate or the people, in general

(3) The Type of Law Administered:

In simple societies the law is unwritten, comprising of folkways, folkmores, superstitions and a reliance on divine revelations or on magic. Folkways are accepted norms of behaviour, the violation of which entails mild penalties in the form of ridicule. Folkmores are also precepts of behaviour in society, but the violation of any of these demands necessitates harsh penalties.

Superstitions arise from a failure to understand the divine or the natural forces in their proper perspectives; while magic stands for a crude understanding of the chain of cause and effect for any matter.

In complex societies, the law is partly written and partly unwritten. Well-established customs and conventions form the unwritten law of the society, while legal principles in writing are found in codes, statutes and Royal Charters. With the development and the advancement of the society, the importance of the unwritten law diminishes; and the more advanced the society is, the more it concerns itself with codified laws.

(4) The Subject-Matter of Law:

Simple societies are formed out of their members’ desires to collect together for the advancement of motives of (a) self-preservation and (b) self-expression. Principles applying in these societies are aimed at securing these motives, and, as a result, the laws applying in tribes or clans cover all the activities of the individual and the society, covering the social and economic activities as also private matters like religious faith and freedom of thought of the individual. One can well imagine a member of a simple society being penalized for being an atheist, for blasphemous utterances or for his inclinations for an alien faith.

In the complex society, laws are made on matters relating to the security of the State, on political matters and on matters relating to property and economic activities. In the more advanced societies, a greater control of economic activities by means of specialized legislation is being exercised, while a new sphere of freedom is being granted to the individual in matters concerning the adjustment of his personal interests in society, like whether or not he would be religious, or he would or not lead a married life and procreate.

(5) The Nature of Sanctions:

No legal principle is worth its sanctity if it is not backed up by an effective system of counter-acting violations. In simple societies, offences of different magnitudes are met with penalties of varying degrees of severity. Ostracism or the disqualification from the membership of the tribe is the severest penalty, second to which comes penalties of mutilations of limbs.

Capital punishment is not considered in such societies as the utmost penalty, though in complex ones it is a penalty that has evoked loud protests on humanitarian grounds. Solemn curses, subjection to magical rites or exposure to ridicule are other examples

of penalties imposed by simple societies.

In complex societies, punishments in form of confinement in prisons or reformatories are very common, a severe alternative being exile, which is a variation of the old practice of ostracism. Fines, payments by way of a penalty to the State, or compensations being payments ways of retributions to the party injured by the act of violation are other alternative. The penalty of confiscation is imposed in societies in which the State power is very exacting.

IV. Religion:

In order to understand religion and religious precepts as an agency of social control, we must first try to appreciate the meaning of the word. The word ‘religion’ appears to have been taken from a Latin root which stands for a ‘bond’ The Indian word Dharma standing for religion emphasizes the quality of ‘holding together’. Hence, religion does not merely connote a belief in God, or a relationship between man and his Creator; it appears that the quality of religious practices that hold society together has a greater significance for the word.

Man’s belief in God must find an outward expression before religion can come into existence, external institutional practices that are associated with it, therefore, have a social significance. Had it been that man simply believed in God and did not consider i necessary to give any expression to his belief, the question of any relations between religion and society would not have arisen. But religion is an institution now and as such it has its importance as an agency of social control.

E.B. Tyler (in his Primitive Culture) defines religion as the belief in spiritual beings, while Auguste Comte identifies humanism with it. No definition of the word can be absolutely satisfactory since the very nature of religion remains clouded human thinking. However, every religion can find a meaning in the importance that it has in a society. Mere belief in God may estrange an individual from his fellows, since he would be liable to apprehend the link between his own self and infinity, other phenomena losing their significance.

But when religion emphasizes the institutional side of it in rituals and celebrations, human beings find an opportunity-1 of assembling together, as in a church or a temple, and bonds of social solidarity are thereby created for the welfare of society as a whole. Moreover, rituals and ceremonies as are devised by religious institutions generate faith in the individual, and the importance of religion in this regard is of no mean significance.

The necessity of religion is as such felt in its contribution to the ideas of the paternity of the Almighty and fraternity of all mankind, as Gisbert puts it in his Fundamentals of Society.

The Place of Religion in Society:

Undoubtedly, the institutional side of religion gains its importance in a discussion of the place or religion in society.

However, for our convenience, we may divide the study into three parts:

(i) Religion through the ages,

(ii) Religion in modern society, and

(iii) Religion in modern India.

(i) Religion Through the Ages:

The early forms of religion came into existence on this earth as a result of a desire to bring cohesion into society, which itself was a product of man’s urge to shift away from the wilderness; but it is undeniable that in far later stages of sociological development witnessed by mankind, religion shaped and modified society in mild as also in violent terms. Palaeolithic man was awestruck by the inexplicable phenomena in the universe, which he tried to explain or appease with the help of magic.

Imperfect faiths based on magic as also on several rituals aimed at quieting the fury of the natural elements have long disappeared from the earth and, one may venture to say that with none of these was present any persuasive and sectioning element that could keep society together.

It is only partly correct to state that religion is based on man’s desperate attempt at believing that he has a soul, that he is immortal It would rather be more cogent an argument that as the principles of ethics were enunciated by human society in order to preserve their acquisitions and to maintain their supremacy over the animal world, the need was felt for some extra-human or supra-social agency, in whose name not only would the subjects in the tribe behave well, but the ruler would restrain himself in his art of governance. As exigency would have it, the need for a spiritual exercise in thought and the imperatives of an ultra-temporal power coincided, and the concept of religion emerged.

Undoubtedly, religion is connected with the concept of God; but in practical terms it is more than that The American anthropologist, William Howells, maintains that man is the creature who comprehends things he cannot see and believes in things he cannot comprehend. No doubt the statement explains man’s attitude of greater reverence towards things that are less known than for objects of recognition; but this factor alone has not given birth to any religion that still subsists on earth.

Man is a religious being not only in the sense that he believes in the Almighty, but also in the light of the fact that he has a half-conscious understanding that the particular belief will sustain him in society. The Hindu distinguishes between Viswas (or belief) and Dharma (or religion); and this dharma is none other than the power blessed by the Divinity that holds society together.

Therefore, religions of the modern world, whether Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity or Islam, have a greater concern for human society than the mere obligation of delineating a super power who comprehends the entire universe. In fact, in the times of recorded history, so great has been, and still is, the influence of religion on man, that societies, nations and governments have risen and fallen – and they still rise and fall – in the name of religion, and religion only, while God Himself is given a clean alibi.

In the closer context of society, it would be noted that all the modern founders of the different world religions have basically been social reformers. Prophets, in ancient Hinduism and Judaism, have been numerous; but whether we take the examples of Abraham or the Hindu human incarnation of Vishnu, the purpose has always been to restore the tilted values of life, much more than to explain to man the very nature of Divinity. Jesus Christ is best looked upon as the Reformer of the Jewish faith though, in effect, he has emerged as the founder of a new religion.

In his exhortation to the Israelites to search their own sins before branding others as violators, he did not pronounce what the world had not known; he merely reminded the people of a sense of logic and ethics which had become blunted by use. Gautama’s teachings, once again, no doubt emphasized the need for Nirvana, but that too was very closely related to the adjustment of human behaviour to the conditions and origins of sorrow and misery.

Mohammed preached the importance of Islam, that of submission to the will of God, in a society of barbarians that desperately needed a greater understanding of what Moses and Jesus had thought earlier, but was lost in the wilderness. Islam is now a religion distinct from Judaism and Christianity, but originally it did not begin with any disrespect for either.

One may say that Mohammed tried to harmonize the social behaviour of the day with the unfailing understanding of an omnipotent and omniscient monotheistic Divinity. Even when Ramakrishna taught in our own country in the last century, he did not arrive on the scene with the desire of establishing a new religion; he merely explained religion in order to clarify certain entangled ideologies that were confounded by the induction of many faiths in the sub-continent.

Once again, when he explained] that all religions lead man to the same path – his eternal home, he merely reiterated 1 the condition of social equality between human beings, a condition in which the use] of any name for our Eternal Father does not, and cannot, downgrade or upgrade any human being.

Every religion preaches the brotherhood of man and, to this extent; every faith is a theological rendering of what later has been celebrated as a communistic innovation. Religion in this sense is more the social relationship between man and man than that between him and his Creator.

Yet the concept of universal brotherhood of man has not encompassed man in a sole, undivided frame of life. While God, in his monotheistic or polytheistic manifestations, has remained the easily identifiable founder and the protector of the cosmos. His followers and believers have come from different parts of the world with differing social backgrounds and sociological sensibilities.

This factor, however, has not given religion the oneness that it deserves; it has fragmented human society into, distinct compartments, at times more hostile and inimical than amiable to each other. This has introduced yet another argument for man’s hatred for each other, xenophobia being the other. It began with the Pharisees of the Chosen Land and then with the several Neros of the West; while Ajatasatrus in the East defiled Buddhist monasteries and recluses all in the name of religion, Judaism stood against Christianity and Hinduism against Buddhism.

This religious feud justified itself in the name of Holy Wars, Crusades and Inquisitions and advanced with merciless rapacity, further reinforced by the Zehads that brought Islam into reckoning both in the East and in the West It is not maintained that with these hostilities the word of God did not spread; what is being emphasized here is that the history of the Middle Ages reinforces the belief that man has used religion to restrict society in bondage and to aggrandize the temporal gains of the physically mighty.

To a man of this century, who has been withstanding the onslaught of science on religions, it seems strange that man has in fact, more often than not, used the name of God in destroying His creation rather than in preserving it.

In the process of segmenting humanity according to man’s psychology about the incomprehensible, mankind has been able to build up a distinct heritage, in each case, of religiosity that has predominantly shaped his social existence. It is commonly maintained that while the Easterner is an introvert, a Westerner is a determined extrovert.

While an average Hindu or a Buddhist looks upon the material world with an attitude of philosophical detachment, a European or an American finds a greater fulfilment in his religious attitudes if he has actually and materially lived well on this earth. These are irreconcilable propositions; and in the modern quest for ‘syncretism’ propounded with a view to placing all religions on the same level, this difference alone baffles the understanding of the one world in the context of the other.

If to a student of sociology it comes as a surprise that millions in India undergo insufferable indignity mingled with penury in their human existence, while their Western counterparts are likely to revolt at the mere suggestion of this sort of a way life, he will find his answer in this fact that the religion philosophical attitude that even the unlettered adopts in this country allows him to accept privations with a calm resignation, the trusteeship of his existence being handed over to God with utmost credulity.

Of course, this attitude accounts for the docile, indolent way of life that an Indian adopts for himself, while the Western world advances with creditable dynamism, but it ought at the same time be asserted that while the Eastern world too is waking up to the needs of industrial, mechanical and scientific developments, the Western world is slowly but perceptively imbibing the reaching or Eastern philosophy.

In the spheres of politics and economics, too, religion has played an important role. In countries like ancient Greece and India, religious practices determined an economic stratification of society. In India, what is now known as the caste system originated with a convenient distribution of labour which, instead of being based on merit, was made hereditary.

In this country as also in Greece and Rome, every profession was given a patron deity, the worship of whom added dignity to every type of labour. Economic reforms that affect religious beliefs have found difficult introduction in society. Only early in this century, Kemal Pasha of Turkey made bold to do away with certain traditional customs and faced as much hostility as the Indian Government has in the later years experienced in trying to obliterate the age-old attitudes of Indians towards family planning.

The effect of religion on politics is more apparent. We, in India, have known how devastating the effects of religious differences may be on the political-social scene. In the participation of sorrows and joys, the Indian lived for over a thousand years together, though not without ugly incidents until, in the consciousness of their modern Western training, the people found themselves unable to live any longer in the same political set-up.

The Arab-Israeli conflict, keeping the centre of our civilized world in ferment, and the Irish scene are pointers to the same unwillingness to compromise with what the other man believes. Hitler’s treatment of the Jews in Nazi Germany perhaps surpasses all the human record of diabolical intentions that are generated by a spirit of vendetta towards persons who profess a different faith.

Customs, traditions and institutions established by religion are different in different countries; but an element of unity which is observed in all the varied practices of different societies is that through the different media of expression man proclaims that he believes in a Power, and that his religious practices are very likely to evoke a very favourable response of that Power towards his society.

Therefore, nature worship as also the reverence shown towards certain rivers and certain animals are forms of expression of faith for the Hindus, while a true Moslem pleases God when he treats every other Moslem as his fellow and brother. The worship of the poor was advocated by Christ Himself and every pious Christian today serves the poor with a spirit of dedication, just as the Hindu texts enjoin upon every householder the duty to treat even the meanest with strict principles of hospitality.

Our debts in society we basically owe to our ancestors and it also becomes a religious practice when we are able to worship the spirits of the departed. Among the Hindus, the Moslems and the Christians, a clear religious ceremony is outlined in a particular part of the year for remembering the dead; and in this respect, the Confucian and the Taoist Chinese of Malaysia and Formosa observe no less important a ritual.

But above all comes the unit of the family. Whatever the religion, society has learnt from it that the elders are to be respected not only for the mere fact that they are at the pivot of the unit, but as a store of experience handed down by generations, to be learnt from and to be transmitted down to posterity, until the possible crack of doom.

In India, a chant hails the father as the very object of meditation, through which religion will be practised and heaven will be attained; while the mother and the motherland have been invested with a glory that is denied even to the Heavens.

(ii) Religion in Modern Society:

Modern religious beliefs, in all their nuances, have shifted from the thoughts of appeasing certain angry spirits whose malefic influences brought misery and bane to human beings. Tribal religion was based on matters and problems relating to procurement of food, birth, diseases, death, fertility of married couples and protection from the weather and wild animals. In olden times, religions might have been confused with magic which was a wrong belief in causal relations between certain practices and effects that were desired.

Today, however, religion has certain specialized connotations which were incomprehensible to tribal man. Modern religion, for example, is not based on any fear-psychosis and does not aim at appeasing fierce powers or deities. When this statement is being made, an understanding of relative modernity is essential, for even today tribal notions of religion are not totally lacking.

Consider the following report for example:

Mob Violence in Shillong:

Shillong, May 31. A large crowd today set a car on fire and damaged the house of a rich and influential woman for allegedly holding a young man captive to sacrifice him to u Thien, a legendary dragon, reports UNI.

Police said a crowd of about 200, which later swelled to thousands, threw stones at the house.

Similar reports appear from Madhya Pradesh relating to the sacrifice of children to appease some God or Goddess. Yet in the midst of this relativity of the concept of modernity, some distinct changes have been noted in the concept of religion in modem times and in its functional utility. First, religion today has discarded polytheistic ideas in favour of a creed for monotheism.

The realization that God is one and indivisible has dawned on every religious thought including Hindu pantheism, which has now accommodated all the different deities under the one umbrella of monotheism. The association of matter with divinity is an old concept; and modem religiosity would rather invest the Supreme Being with spirituality than with material attributes such as strength, values and the ability to wage gargantuan battles.

The modern deity is the epitome of all moral qualities and all mankind can look upto him for inspiration and direction in matters of moral behaviour. These moral qualities have invested value judgments upon man-king and religion has become the virtual custodian of values; religiosity now stands for the upholding of such values in individual and social life.

Secondly, modern religion no longer becomes a vehicle for establishing relations with God when one is in need. Primitive people prayed only when they wanted to be saved from perils and when a plenty in food production or the propagation of the tribe was sought; it did not occur to them that the Divine could bless them with a noble and meaningful way of life. Today, religiosity stands for everything that is ethical, moral and noble in life.

As has already been pointed out, the very meaning and purpose of religion today is found in ideas like brotherhood of man and general welfare of mankind. In this regard, primitive religion might be taken to have been self-centred; today, it is selfless and liberal to such an extent that the talk of unity in diversity is being reflected in comprehensive faiths like syncretism. Charity, hospitality and generosity might have existed in human behaviour since olden times, but these concepts have found their real meaning in modern man’s religious sensibilities.

Thirdly, devoid of orthodoxy and superstitious rigidity that accompany conservatism of the mind, religion has risen above mere rituals, though we have noted that institutionality of religious practices gives it a social meaning. According to McIver and Page, rituals stand for a rhythmic procedure that is directed to the same end and is repeated for lending solemnly to the act. Rituals still find their significance and importance in life because of the myths they carry and the symbols they associate themselves with.

Symbols are an age-old attraction for man, and his obsession with a symbol of an animal like the bull, the serpent or the elephant-head has been described as ‘Totemism’. Though totemism exists in some manner or other in our social behaviour, as in cases of out identification with mascots or insignias, modern religious concepts have been freed of totemism.

Religion is no longer the same as magic and, today, prayers are primarily repeated assertions of the fact of supremacy of the Divine and man’s dependence upon Him in all respects. To obtain the ‘Grace of God’ is the aim of a noble life and in the midst of all perversity and permissiveness, of the modern world, nobility cannot be said to have been totally forgotten. The rituals for modern man are therefore simplified and all elaborations are regarded as synonymous with redundancy.

Lastly, more and more man-king becomes conscious of the loftiness that religiosity stands for the institutional character of religion as a group practice is losing its importance to the idea of individual upliftment of the mind. Ever since Charles Darwin shattered the Biblical concepts of the origin of the world, the human mind wavered between the desire to submit to science and the will to worship an unknown power as the Almighty.

Alfred Tennyson’s Victorian compromise effected between assertions of Divinity and scientific knowledge brought a sense of calm to the nineteenth century human mind. Today, the tradition of Tennysonian compromise continues with us and except to the atheist, all scientific knowledge appears as a part of a design that has been woven by Divinity.

In the world of technology, this creed lies at the basis of the continued efficacy of religion as an agent of social control. Ceremonies and rituals are no longer considered to be relevant; if they are observed, at best they manifest our desire for showing our reverence to our ancestors.

Today, modern man by a majority believes that religion is his personal faith and that he can afford to be as religious in his ways of life by praying by himself as he can be when he becomes a participant in a community worship. But, to a sociologist, community worship and institutional religion are matters of interest, for he finds in such, and not in prayer monologues, a point of social significance.

(iii) Religion in India today:

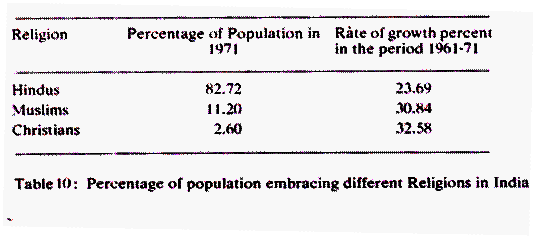

According to the Census of India 1971, the following picture emegres of people following the major faiths in our country:

Modern India, that is made a Secular Republic by its Constitution, contains a population that, in different percentages as shown above, belong to different religious groups, besides Hinduism, and these together accounted for 3.42% of our population in 1971. The Hindus form the largest religious community in our country along with several variations and fragmentations from the original faith, including the Buddhists, the Jains, the Sikhs, the Arya Samajists and the Brahmos.

The Muslims in India predominantly belong to the Sunni sect of the religion, while the Christians, though they account for about 2.60% of our population, belong to not less than 60 denominations of the Roman Catholic and the Protestant divisions. Of the 1.4 crores of Christians today living in the country, about one-half are Roman Catholics. Catholics are more numerous in Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Goa, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal than in other places.

The Protestants are better distributed throughout India. As many as 60 Protestent denominations in the country include the Church of South India, the United Church of North India, the Baptists, the Lutherans and the Marthomites. While about one-fourth of the total population of Goa, Daman and Diu follow Christianity, 344, 798 out of 516,449 people inhabiting Nagaland are Christians.

The Republic of India does not seek the promotion of any religious interest, though the State does not prohibit the practise of any religion. Article 25 of the Indian Constitution states that, subject to public order, morality and health, all persons are entitled to the freedom of conscience and the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion.

Herein lies the very essence of the seculat character of a State and, as a further guarantee to religious freedom amd toletance, other provisions has been made. It is punishable to promote enmity, hatred or ill-will between classes and religious communities, and such acts have been made criminal offences under Section 505 of the Indian Penal Gode.

Article 26 of the constitution guarantees of Indians the freedom of establishing and maintaining institutions for religious and charitable proposes. Religious minorities have, under Article 30, the full freedom of establishing and administering educational institutions of their choice. Neither will the minority be deprived of State assistance merely on the ground that they endorse certain religious views, nor will any one be subjected to payment of any tax, the proceeds of which are to be used for the promotion or advancement of the cause of any religion.

Article 29 prohibits discrimination in admission to educational institutions on ground only of religion, race, caste, language or any of them if such institution is maintained out of State funds. However, lest it appears that the State is patronizing any of the religions followed by Indians, Article 28 has made it very clear that no religious instruction of any brand or type can be imparted in any institution that is maintained wholly with the help of State funds. This does not prevent minority institutions from imparting such education, even though they are in receipt of some State assistance.

All that appears above is State policy and the letter of the law. In actuality, differences between creeds are only of obvious manifestations. While the Hindu believes in God as an entity, the Jain or the Buddhist follows principles of morality, but no Almighty. The Hindu creed entertains polytheistic thoughts and, even from the Vedic times, Hindus have been worshipping many Gods and Goddesses who are capable of taking several forms.

Idolatry, therefore, is a part of Hinduism and, in this respect; the creed is diametrically opposed to Islamic thoughts of a formless Almighty- power who cannot be conceived of as an incarnate being. Idolatry is a grave sin with the Mohamedan, much more than it is to the Roman Catholic.

The Catholic is not an idolater in the sense the Hindu is, but he does not totally discard the image of the Almighty as also material representations of the Virgin and the Christ himself from his modes of worship. Therefore, diversity of religious thoughts and the harmonizing of all beliefs and creeds with at least the virtues of tolerance seem to be the theme of Indian living. To deny occasional outbursts of vicious hostility of one community for the other would be pretence of a very degrading nature; but laying emphasis upon such discordant notes in the mode of Indian life would be little short of shameless propaganda.

The truth is that, in India, co-existence of several communities together is more a practical possibility than it is in many countries that lift their finger of accusation against the Indian nation on the count of communal disharmony. What Emperor Akbar tried to achieve through his composite creed of the Din-e-Elahi was an attempt at giving formal and external recognition to a fact that all faiths together effect a unity of thought that God is divine and that He is the Creator of all universal objects. It is more important to appreciate the fact that Indians have by and large applied this theme to their everyday practice and matters of social intercourse.

It will be interesting to note in Indian way of living the following features which happen to be a distinct contribution of the various religious thoughts that we subscribe to:

(a) Though the Hindu follows Hinduism, the Muslim adheres to Islam and the Christian upholds the teachings of the Christ, together they represent a common attitude of religiosity. Every Indian is a religious individual and he, in his own way, agrees with his brother that the Divine Being controls all.

(b) Since every religion teaches the right conduct and the ethical basis of proper human behaviour, an average Indian can effect a unity of thought with his brother belonging to another faith.

Religious differences cannot interfere with standards of ethics and religious practices prescribed for every community inspire the devotee’s conduct with ethical ideas and lofty norms of behaviour. When the Muslim engages in fasting during the month of Ramzan, the Christian mourns with austere practices the Crucifixion of the Christ during Easter, and when the Hindu fasts in remembrance of his ancestors or while he makes worshipful offerings to God, they are all admitting the value of a good, noble and moral way of life.

(c) All faiths in India subscribe to the view of fraternity of man and it is believed that, within the limitations of different creeds and religious beliefs, every man stands as brother to his fellow human being. The concept of a secular republic is, therefore, not thrust upon the people of India; the Constitution of the country merely gives official recognition to the free will of all its nationals.

(d) Charity is regarded as an act of high virtue and religious sensibility by the religions of India and, in this regard, these different creeds have affected a unity of theological thought. Like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, an average Indian firmly believes that

‘He prayeth best who loveth best, both things great and small. For the dear God who loveth us did make and loveth all.’

Religion and Magic:

E.B. Tyler, in his Primitive Culture, defines magic as an elaborate and a systematic pseudo-science. In it certain beliefs were given practical expression in everyday affairs in the older times and the objects of magic might be food production, a voyage, childbirth or even the desired death of an enemy. Magic as a kind of a knowledge or art was never required to come into play as long as natural forces like wind, rain, fire and herbs could do the work they were expected to do.

But when these forces failed, the magician came forward with his supposed control over them; and in certain tribes the prevalent belief was that he could control even the gods who had to act according to the strength of the spell. Hence, the magician enjoyed immense prestige in primitive societies; and several marks and emblems were made out on his person in order to protect him from evil.

It has been the endeavour of several students of magic to locate a method in it. By and large, magic is an individual art that is handed down from man to man through the generations, and that art was believed to have been related to the supernatural elements. J.G.Frazer writes in his Goldern Bough Part I: Early History of Kingship that the practice of magic was based on the law of ‘sympathy’, which operated on either of two principles, the principle of ‘similarity’ and the principle of ‘contagion’.

According to the principle of similarity, it was taken that if there was any resemblance between two objects, they were one and the same in element. Thus, if a wax doll of an enemy could be hit with thorns or sharp instruments as magic spells were uttered, the belief was that the man himself would die. Similarly, if rain was sought amidst drought conditions, sprinkling of water to the accompaniment of a recital of charms was thought to be effective for bringing about the desired effect.

Again, when the principle of contagion was applied, it was believed that if two objects had at one time been together, their subsequent dissociation from each other would not obliterate their original link; and if one of them is placed under any magic spell, the other would necessarily feel its influence. Thus, if an enemy’s nail, hair or excreta can be cast under a magic charm, the individual himself would suffer from its malefic influence.

The procedure in invoking magic powers had also certain definite elements or features in it and these comprised of (i) the ‘recital’ of charms, (ii) the set ‘acts’ required to be performed in each case and (iii) the ‘matter’ or the ‘object’. The matter was either actual or representative. In other words, with some kind of knowledge of medicine and surgery, the witch doctor could perform magical rites upon the patient himself, which could be a mode of auto-suggestion for obtaining desired results; or he could take an object that would represent the man upon whom the magic spell was to be cast.

The action in magic took various shapes and forms, and varied from mildly touching the object with a wand to violently striking it depending upon the viciousness of the magician’s purpose. Of course, he was not always vicious; he could be benevolent also when he sought to improve the yield of crops with the help of his magic. His purposes could range from private vendetta to public and social service, the latter being more noble and in the least degree harmful.

The magic charm had to be uttered with special skill which only the magician possessed and much of the effects of magic depended on whether or not the words were recited with perfection. Herein lay the secret of his trade which he would not share with any person other than his true successor, and techniques like uttering all the words of the chant in one breath might have had some connection with bluff or subterfuge.

The prop of magic was the strange or the inexplicable. R.R. Marett writes in his Threshold of Religion that Melanesians believe in a mysterious occult power known as the ‘mana’. Mana is believed to be a supernatural power or quality in an object that makes it behave in an inexplicable manner.

For example, a piece of stone will be taken to possess the quality of the ‘mana’ if it can influence some other object like a woman or a plant and can make her or it fertile. But then ‘mana’ is not magic truly speaking, since magic must be performed by an individual and mana is a mysterious quality possessed by an object.

Magic and magical rites may at times be confused with religion and religious practices. Both religion and magic are concerned with those elements of human experience that lie outside his power of control over natural forces. In ancient religion the attempt was to please a God with rites so that he blessed the devotee; and the magician among primitive people applied his spell to a spirit or a demon who would secure for him all the effects that he was applying for.

Frazer believes that religion followed magic, particularly when the magician failed in his efforts and the clever in the tribe understood that he had no actual control over the forces of nature; perhaps the magician too admitted his limitations and thought of appealing to the Gods for the good of mankind. Some other writers point out that though magic was and still is, more predominant in primitive societies than religion and that occult and magic charms were, and still are, similar to those of primitive religious rites, the observation made by Frazer need not be taken to be fully correct.

Magic has, at all times, concentrated its attention upon matter and has tried physically to influence its activities. Magicians believed that they could keep material objects, and even gods, under their control by placing them under magic spells. The priest on the other hand offered prayers and scarifies to a supra-natural power who was known as a God and sought its blessings, the very posture on his part admitting that the power was a superior one and that it could not be controlled by occult practices.

In some primitive societies, the same individual acted both as a priest and as a magician, and these were the stages when religion and magic were almost identified. The offerings of animals as a sacrifice to appease a God in ancient India could be taken as instances of the confusion of magic and religion.

According to Frazer, when primitive man woke up to the consciousness of existence of gods, such gods were initially considered to be either as powerful in magic arts and acting as the presiding deities over magic, or as magicians themselves. In some cases, human magicians came, after their death, to be worshipped as gods. Frazer tells us that in old Australia, religion was not conceived of as any entity that was distinct from magic; ancient Australian tribes had only magicians and no priests.

When magic had its sway over ancient communities it acted as an agent of social control, and the fear of a magic spell could even go to the extent of causing morbidity in an individual. As an agent of social control, it acted in a manner that was different from the modus operandi of religion. Magic was based on the fear of the unknown and the grotesque; it indicated a spirit in all objects that could have its benefic or malefic effects and such effects could be excited, directed or controlled by the magician’s art. Religion, too, was in ancient times based on fear, but the fear of an unknown power that stood above all human forces.

It had to be appeased with offerings and prayers but, in this regard, no human being had any power of predictions of the divine will. While magical rites were primarily individual – based in the sense that the participant in them was the magician only, religious rites comprehended the entire society in participation and as such, religion acquired a greater social significance than magic.

Religion and Morality:

The concept of religion and morality must best be kept s apart. Morality means conformity to the laws of ethics, and ethics are a social understanding of right and wrong. Every individual may, however, have a sense of ethics but unless his understanding of ethical principles coincides with the understanding of the same by his society, the true concept of right and wrong is not likely to emerge.

Ethics is not religion, at least, not necessarily so; for one can be a atheist and yet have a strong sense of right and wrong and being religious does not necessarily imply that one’s sensibilities are in line with ethical philosophy. Morality seems, therefore, merely to be an attempt of human beings at regulating their course of action in accordance with the dictates of nature; it is an effort at bringing harmony between conscious human acts and the order that the sun, the moon, the stars and in fact, all things universal follow.

As we assert so frequently, ‘there is an order in nature’, so we try to translate this belief of ours into our actions when we call ourselves moralistic. Of course, there are different versions of ethical principles available in different communities but, minor differences apart, all communities endeavour to bring to human life a natural order. Perhaps, that is the very essence at ethics.

Religion cannot but teach the same order in things when it admits human subordination to the Almighty and the universal brotherhood of man. Religion, therefore, encourages ethics without being an institution of morality itself.

In fact occasionally when unscientific religious practices ordain maiming rites, human sacrifice or offering the first-born to Mother Ganga, besides declaring certain types of foodstuff with hygienic value as unsanctified, it is not following ethical patterns; and in our country the concept of preserving one’s religious virtue by shunning the contact of non-Hindus is morally outrageous.

Yet, by and large, the teachings of religion and ethics are the same, and such lessons are regarded as conducive to the growth of healthy relationships between individuals who live in society. The difference between the two becomes apparent when one takes into account the nature of sanctions applying in either case or the respective authorities that are empowered to impose the sanctions.

Religion places before society ‘supra-social’ sanctions for the detractor of religious precepts, the priest acting in the name of God being regarded as the authority, who would specify the nature of penalty that goes with an act of sin. Moral codes have nothing to do with God, although modern religion takes ethical behaviour as virtue and violations of morality as sinful.

Morality is based on social considerations of good and evil and, in order to sanctify ethical values, perhaps at a certain point of social development all moral considerations were pronounced as commandments of God Himself. In this context, one must remember that only such religion has stood the test of time which has been beneficial to society and social relations; and social relations prosper well when ethics govern human conduct. We are not in a position to state whether, in the course of human social development morality preceded religion or religious growth led to moral understandings.

One does not feel that going into the controversy is a needful activity. When Auguste Comte asserts that religious consciousness preceded ethical understandings, or when Emile Durkheim states that religion came to sanctify moral ideas, neither is speaking the whole truth. Even primitive people with religious sentiments had ethical preferences for life and it is not until our rational times that the conflict between the two, if any, has been emphasized.

When religion divides humanity into different segments, social welfare as a whole cannot be conceived of in any community that takes the shape of a complex society- today. In our complex societies, different ethnic and religious groups must exist together, and the new concept of the morality of ‘humanism’ requires a new social and religious code based on tolerance of every idea, faith or creed so that social welfare for humanity as a whole becomes the keyword of ethics.

Religion is itself being purified not only of all its conservative approach to innovations and discoveries, but also of its hostility to the integrating process in the conscience of modern man and, if that process is ever completed, it would speak of the supremacy of ethics over sectarian creeds.

Mythology and Social Behaviour:

It is fitting that in the context of certain countries like India, a discussion on mythology be appended to the study of religion Mythology, in the truest sense of the word, represents the incredible, and must have found its origin in those inquiries that puzzled early man about the origins and the beginnings of mankind and their possible conditions after death.

Yet apart from the fact that myths have always sought to explain what remained inexplicable till science, to a large extent, dispelled the doubts, there is a clear understanding that these stories told more about man himself than about the unknown. Myths of different times and of different, regions of the world give an account of traditional rites and customs observed by men, and the student can easily get an insight into the type of society that he has placed under study.

More often than not, mythical stories tell about ancient man’s environment and society in which he lived as also his psychology which, curiously enough, he himself did not appreciate. Gods and goddesses conceived of in yester years were human beings drawn on a larger and a grander scale so that they could be invested with super human capabilities and, at times, as in Indian mythology, repetition of heroic feats, with or without embellishments, in the course of time transformed actual human beings into deified personalities.

Certain characteristics about mythical stories explain how the geographical environment, in each case, modified the over-reaching imagination of early man in giving shape to his concept of the unknown which, to simple mind, was the supernatural. First, the climate of a particular country played an important role in depicting the regions of the dead or those that were inhabited by the gods.

In the cold north, a mythical cow named Audumla caused the birth of man by licking frozen stones, while the region of the dead was a bare and misty plain where shivering and hungry spirits merely wandered about. The Greeks ascribed to Prometheus the task of raising the first human being from clay on a flowery river bank, which had a much fairer climate than northerners conceived of. To them the afterworld was either a dark cavernous region meant for the slaves or the Elysian Fields that welcomed the nobler and the royal soul.

Early Indians, to whom the mighty Indus and then the Ganga must have presented much hindrance and misery mixed with dismay, almost unfailingly conceived of the void as a huge flood of water from which emerged Lord Vishnu and the Creator Brahma collectively to execute their designs of bringing into existence a new kalpa of mankind.

In China, according to Taoist legends, the God in charge of mankind lived in the mountain Tai-shun in Shantung, and was known as the Great Emperor of the Eastern Peak. In Polynesia, the creator of the world, Tangaroa, lived (or still lives) in surroundings which are not strikingly dissimilar to the island surroundings.

African mythology, which by and large accommodated the natural elements and forces as divine powers, nevertheless accepted a supreme God who created the first man and first woman. The natural surroundings of Africa find expression in the Malagasy myth that the son of God, sent to earth on a mission by his father, found the Globe so hot that he plunged deep to find a little coolness and never appeared again. Man comes to this earth, even to this day, to search for Ataokoloinona, the son of God, and return after a fruitless search to report to God; and their departure from the earth is known as Death.

The connection between mythology and the society that created the myth is also explained by the fact that animals and birds, quaint, monstrous or even terrifying, abound in anecdotes, and animal gods are by no means inferior to human shaped gods in their physical power and magical or ominous attributes. Several gods of the Egyptian Pantheon possessed animal shapes, or even shapes that contained the attributes of human beings mixed with those of birds or animals.

Efu Ra, the dead sun, was portrayed as a man with a ram’s head, while Horus, the Solar God of Memphis, had the head of a falcon affixed to a human body. Anubis, the God of the cemetery, was either a jackal or a human with a jackal’s head. The protective Gods had as their head Amon, the king of the gods, who was represented first in the goose form and then in that of a ram.

The Hindu Ganesha and Garuda are both celestial beings that show a combination of both human and animal forms. The Greek satyrs, centaurs or minotaurs, though they did not enjoy the status of gods, were nevertheless supernatural or celestial creatures in the same measure as Yakshas, Gandharvas and the Kubera were concerned in the Indian mythological scene. The Greeks and the Indians, however, chose to appropriate different animals or birds to different deities as their cup-bearers or bearers of their chariots.

While this line of thinking must have necessarily emphasized the then existing close association between human and animal existence, the gods with fearful animalistic attributes, like Rahu in India and the four Dragon-kings in China, represented the awe that human beings had for their predators.