ADVERTISEMENTS:

This article provides information about the contemporary social theory in the light of environment concern:

The more recent concern of the causes and consequences of the present ecological crises are significant to modern social theory. The relation between human beings and nature and the deleterious effect of human action upon the latter, a hitherto neglected area, has emerged as a major issue.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Another important issue in contemporary theory is the growth of environmental politics/movements which pose a challenge to the modern industrial/capitalist mode of production and consumption which are essentially environmentally destructive.

Anthony Giddens, in his later works, attributes environmental problems to the modern industrial societies and the industrial sectors in the developing countries. Whatever the origin of the crisis, the modern industry, shaped by the combination of science and technology is responsible for the greatest transformation of the world of nature than ever before.

Ulrich Beck distinguishes the modern society from the earlier ones as the risk society, characterised by its catastrophic potential resulting from environmental deterioration. In the pre-industrial societies, risks resulting from natural hazards occurred and by their very character could not be attributed to voluntary decision-making.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The nature of risk changed in the industrial societies. Industrial risks and accidents at work sites, or dangers of unemployment resulting from the changes in the economic cycles, could no longer be attributed to nature. These societies also developed institutions and methods to cope with the dangers and risks, in the form of insurance, compensation, safety, etc.

The risk societies are characterised by increasing environmental degradation and environmental hazards. “At the centre lie the risks and consequences of modernisation which are revealed as irresistible threats to the life of plants animals and human beings. Unlike the factory related or occupational hazards of the 19th and first half of the 20th century, these can no longer be limited to certain localities or groups, but rather exhibit a tendency to globalisation”.

In the face of environmental risks and hazards of a qualitatively different kind, both real and potential, earlier modes of coping with them also break down. Yet when large-scale disasters like “Chernobyl” occur, protests do break out which challenge the legitimacy of the state and other institutions that appear powerless to manage the problems. Giddens offers two explanations for the emergence of environmental politics – as a response to the ecological threats and thus “a politics mobilised by ideal values and moral imperatives”. Ecological movements, he observes compel us to confront those dimensions of modernity, which have been hitherto neglected. Furthermore, they sensitise us of subtleties in the relation between nature and human beings that would otherwise remain unexplored.

Habermas sees the ecology movements as a response of the life-world to its colonisation. Since they are an expression of the reification of the communicative order of the life-world, further economic development or technical improvements in the administrative apparatus of government cannot alleviate these tensions. For Habermas, capitalism is the primary cause of environmental degradation.

All these social theorists emphasise the need for democratisation of state power and civil society. Giddens suggests that not just the impact, but the very logic of unchecked scientific and technological development would have to be confronts if further harm is to be avoided. He argues that since the most consequential ecological issues are global, forms of intervention would necessarily have a global basis. New forms of local, national and international democracy may emerge and form an essential component of any politics that seeks to transcend the threats of modernity.

Habermas, while recognising the limitations of modern state power, argues for the creation and defence of a public sphere where rational democratic discourse can occur. Beck argues for an ecological democracy as the central political response to the dangers of the risk society. Research agendas, development plans and introduction of new technologies must be made open for discussion and at the same time legal and institutional controls on them must be made more effective. All the above scholars point to the limitations of the pre-dominantly representative rather that participatory character of liberal democracy being an essential pre-condition for creating environmental sustainability.

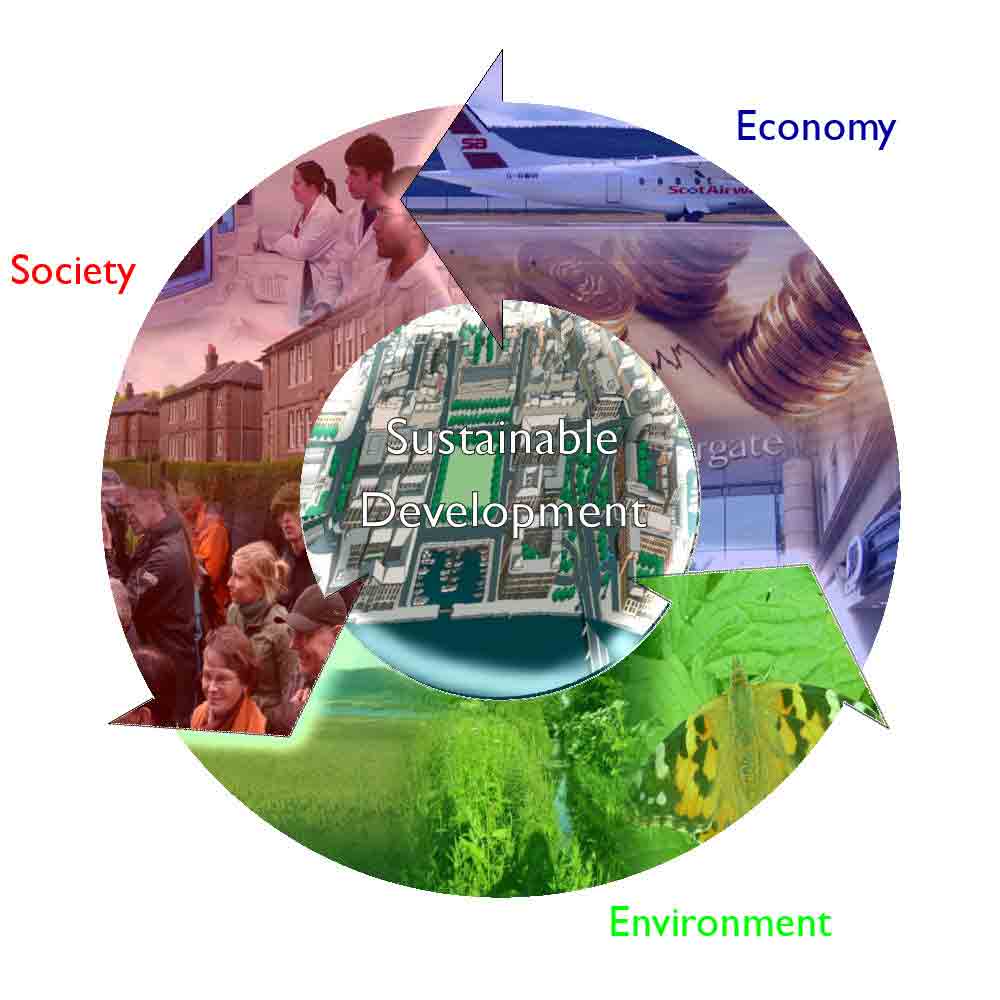

A sociological/social science perspective in the analysis of environmental issues is still emerging. Responding to the demands of social reality, sociologists are just beginning to explore the many dimensions of the environmental problems of our times. The ecological/environmental perspective opens up the unexplored dimension of some of the important areas of sociological concern. As powerful critique of the modernisation/development agenda, this perspective brings out the unsustainability of the project. The industrial capitalist mode of production and consumption destroys the very resource base necessary for its existence, but even more, threatens human life itself.

With the growth of ecological politics and movements, a new area of sociological enquiry has opened up, which transcends the conventional dichotomy of the right and left politics, that cuts across class divisions and even national boundaries and creates spaces for activism within the civil society using the popular initiative. In a fundamental sense, it calls for a redefinition of the relation between human beings and their natural environment and a reconsideration of the effect of human action upon nature.